Francis Lagrange

Francis Lagrange

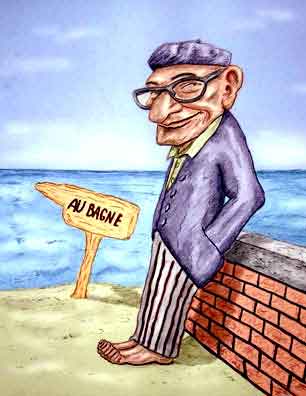

Le bagne - pas une colonie des vacances.

Devil's Island. Hell on earth. A place where many men, unjustly convicted and outcast by society, were subjected to the daily brutalization of torture, disease, starvation, and murder. Many went in, few came out. Devil's Island - an iconic memorial of man's inhumanity to man.

But today, due to the many sensational exposeés, documentaries, films, and now the electronic media, we know the TRUTH and the horrors of the dreaded Devil's Island.

Vraiment?

Weeeeeeeeeellllllllll, not quite, said Francis "Flag" Lagrange, art conservator, stage set designer, art forger, counterfeiter, and finally inmate for 15 years in le penitencier de Guyane francaise. For one thing, Devil's Island is really only one small island about 10 miles off the country's coast and only held prisoners convicted of treason. These prisoners were few and far between, and at any one time there were no more than a handful in residence on Devil's Island proper. And far from being ill-treated, abused, and starved, they were better housed, better clothed, and better fed than most of the other inmates. For the most part, they were left to themselves.

But as far as the overseas penitentiary in French Guiana itself - the infamous bagne - it was not just one, but a series of prison camps. The largest of these was at St. Laurent-du-Maroni across the river from Dutch Surinam. That's where the inmates arrived on board the transport ship La Martinière. There they were sorted and dispatched to their assigned camps.

A number of prisoners remained in St. Laurent or were sent to the sister camp at Cayenne, the territorial capital about a hundred and sixty miles east-southeast and along the coast. Less fortunate convicts were sent to the work camps in the jungle. Admittedly, these were not nice places. The individuals who were considered particular escape risks were sent to the islands of Royale or St. Joseph, two of the three Îles du Salut - the Islands of Salvation. The Île du Diable, or Devil's Island, was the smallest, which as we said, was reserved for prisoners convicted of treason.

What was life like in the bagne? Flag was specific and emphatic. It was no worse than any other prison for the era, and in some ways it was better. But it was, he said, a penitentiary, not a summer camp - pas une colonie des vacances. Measures were needed to control large numbers of men, many of whom were not particularly nice. And as in prisons then and now, much of how the men fared depended on the manner, philosophy, and honesty of particular officers and guards. Even then, having a martinet in charge did not mean the prisoners suffered. One no-nonsense commandant - who was really had a cul refractaire - nonetheless treated the men fairly, Flag said.

That doesn't mean there were not cases of brutality. But they were, Flag insisted, individual acts by individuals and were the exceptions, not the rule. The only time Flag encountered institutional ill-treatment was during World War II. After Hitler began his marches, the part of France that was - quote - "unoccupied" - unquote - and run by the French Vichy government remained in charge of Guiana. This pro-German government dispatched a gung-ho commander to run the prison. Actually he had been sent to Guiana because his superiors found him so incompetent they thought that was the best way to get him out of their hair. He overworked everyone and punished even minimal infractions (real or imagined) severely. All in all he made life hell. However, when French Guiana switched allegiance to le grand Charlot (i. e., Degaulle) the tin-plated mini-dictator was shipped back to France where Flag believed - or at least hoped - he suffered the fate of other German collaborators.

The bagne was not, Flag admitted, a model for prisoner rehabilitation or penal professionalism. In the 1930's few prisons were. Black marketing was universal and usually operated in collaboration with the guards. The guards, it should be remembered, were generally from poor familes and took the jobs in Guiana as a way to achieve some measure of prosperity and security. But personal problems between the men - guards and convicts - often created very tense situations. Inmate-on-inmate violence was common (as it is today), and yes, there were cases when guards abused and even murdered inmates. The reasons were varied. Sometimes the guard was simply a sadist. Other times the guard and prisoner may have been in cahoots in some skullduggery and getting rid of one or the other was the way to keep things under wraps. Then there was always the pesky little problem where the guards' wives easily found the prisoners a bit more to their liking than were their husbands. It wasn't unheard of that a guard would come home unexpectedly to find his sweetie and a bangard in flagrante delicto. In such encounters, the prisoner almost never (no joke intended) came out on top.

And escape? Actually that was the easy part, Flag said, at least for prisoners kept in St. Laurent. As long as you behaved you were likely to be assigned a job in the town. Furthermore, the labor was largely unsupervised. Working at the leisurely "colonial" pace, the men swept the streets, trimmed the trees, tended the gardens, painted houses and fences, and more or less kept the town looking like a charming overseas departmental paradise. And just across the river was Dutch Surinam.

So the easiest way to escape was to simply walk out of town and pay one of the river boatmen 100 francs to row you across the river. Then the usual procedure was the Dutch police would arrest you and return you to Guiana. Getting away was easy. Staying away was something else again. Very few managed that.

Despite Flag's fairly mild assessment of Guiana, it gives the reader pause when you hear the prison population was fairly stable, and yet 1000 - 1500 prisoners arrived each year. Population of the convicts in 1901 was about 4000 active prisoners and about half that many freed convicts - the libérés. But being freed didn't mean a return to France. You still had to serve out your doublage - that is a time equal to your sentence - in French Guiana. If your sentence was more than eight years, you had to remain in Guiana the rest of your life.

The biggest killer, though, was certainly disease. Malaria, scurvy, and leprosy were commonplace. Although there was an honest attempt to provide the prisoners with medical care, during the early to mid-Twentieth Century, treatment of disease and injury was still often rudimentary. In these pre-antibiotic days even small cuts and scrapes could develop into life threatening infections.

Whatever the reason attrition was clearly high, with around 20 % of the men somehow disappearing per year only to be replenished with fresh transportees. Flag's information is consistent with this estimate. He said probably 25 % of the inmates were under medical care at any given time and maybe 25 % were in the bush trying to escape (and dying or being recaptured). So that would require somewhat less than half of each group to disappear.

There were also the incos or incorrigibles, and Flag put their population at about 25 % as well. These men were kept chained in barracks during the day - a very unpleasant existence in the tropics, and these were also the men among which inmate murders were highest. But, Flag added, the incos had been so classified mostly because they were rebellious and refused to obey the guards and other officials. So their lot was largely their own doing. That left the remaining 25 % who were "normal" prisoners and who, if they wished, could make life bearable by doing what they were told and avoiding confrontations.

Flag's book appeared in 1961 and later accounts by others have suspicious similarities. For instance Flag tells of how during one of his escape attempts he was given assistance by an Indian tribe. These were not, by the way, the unspoiled, isolated "noble savages" of popular legend. The tribe traded with local villages and marketed game and fish in St. Laurent and other towns along the river. The chief was a knowledgeable and savvy leader who spoke French. The tribe took to Flag and invited him to remain. When he declined, they rowed him upriver to where he could move into British Guiana where he was captured under rather amusing circumstances.

Flag also told how some prisoners tried to craft makeshift rafts to escape from the Îles du Salut. In particular he told the story of a Russian prisoner (note, that's a Russian prisoner) who constructed a raft by stuffing a bag full of coconuts and then floated to the mainland. He was captured immediately, but if this sounds familiar, it should.

Which brings us to the most famous account of "Devil's Island", at least to American audiences. In 1969, Henri Charrière published his best seller Papillon and told of unspeakable horrors where guards would beat inmates to death free of any fear of punishment, inmates would be placed in solitary cells up to eight years, kept locked up 24/7, denied medical attention, and not permitted to speak to anyone. He also told how in his own escape he was aided by an Indian tribe and how he was invited to stay. And as all the world "knows", Henri escaped from Devil's Island by floating away on a bag of coconuts.

Henri Charriere - Papillon

He wrote a novel.

As should now be no surprise, then, the story of Papillon has been shown to be a fictionalization using borrowed adventures and is not a literal autobiography. But the account of some others, particularly that of Rene Belbenoit, in his famous Dry Guillotine, also told of horrible conditions and brutal guards and officers. Part of the discrepancies, Flag said, was simply sensationalism; the desire to sell books and film rights. That doesn't mean Rene was necessarily lying, said Flag, but the worst horror stories most likely came from the work camps in the jungles. There without any oversight of upper level officers, a brutal commandant would literally work hundreds to death.

One point to remember is that "Devil's Island" lasted from 1851 to 1948. In that time treatment of prisoners and philosophy of rehabilitation changed. So a story from the 1920's - about how the reclusionaires in solitary were never allowed out of their cells for the duration of their sentences (actually limited to five years) is indeed true. But it's also true that this was not the case by the 1930's when Flag was transferred to the islands (which was for fiddling around with the commandant's girlfriend rather than any real infraction). In Flag's day, the prisoners in solitary were allowed out of their cells during the day to work around the islands. They were still not permitted to speak to each other, but their time was spent more like that of other prisoners.

So what was the bagne really like? If the impartial readers plow through the various books about "Devil's Island", they find essentially the same story but told from different viewpoints. Which brings us to an important point about Flag, and a point he even mentions explicitly. Flag was a well educated man with training as an artist, and in prison he was given extremely cushy jobs. Even after his escapes, he was assigned work like painting signs and making portraits of the officers' wives and families. Flag was even given leave to go on a coastal mapping expedition with the French navy, and he was assigned to be an academic tutor to the troublesome son of the camp commandant. The boy later began a successful career in the army and befriended Flag after Flag stayed in Guiana after his liberation. So Flag was able to avoid the worst aspects of the bagne, and this certainly colored his opinion.

Finally before nous americains thump our collective chests about how much better we have been regarding criminal rehabilitation compared to our cousins français, we should pause and remember that in one point Flag was undoubtedly correct. "Devil's Island" was no worse than many of the penitentiaries of the era - and that includes those in the United States. In particular, prior to World War II the southern penitentiary system was one of extreme brutality (although some big houses in the north were probably not much better). Among the most incredible (and deliberately ignored) episodes in America is the era of convict leasing, particularly leased convict labor for the mining industry. The convict miners lived in unspeakable conditions and were required to mine as much as 14 tons of coal a day when perhaps twenty years later the expected quantity for a free miner on wages was four tons. Post-bellum mortality among leased convicts could run as high as 40 % a year. Although the last convict mine was closed in 1928, convict leasing remained in various forms until after World War II.

So why do virtually all Americans remain blissfully unaware of the leased convict era in American history and of the convict mines while the unspeakable horrors of "Devil's Island" remains so much a part of American mythology? A number of reasons. First, the worst prisons were by far the southern penitentiaries. Since they were regional, not federal, prisons it's easy to dismiss them as atypical. Regional they were; atypical, no. Worse, the southern prisons were part of systematic and deliberate repression of one race by another, historical dirt that that even today many Americans would like to sweep under the rug. But the final reason is quite simple. We'd rather air out France's dirty laundry than our own.

References

Flag on Devil's Island, Francis Lagrange and William Murray, Doubleday (1961). Flag's book is entertaining and is unique of all the "Devil's Island's" books in claiming life was not always the unmitigated horror of popular legend. At the same time most other books by other ex-inmates, also show life ranging from the brutal to the almost tranquil - within limits that is. So in that sense, the discrepancies aren't as great as might first be supposed.

Lest some look on the claims by Flag as a revisionist whitewash, remember Flag was an inmate. He had nothing to gain by painting a milder particular picture of the bagne, and in fact his book may have sold better if he had gone the usual route of saying Devil's Island was a place of institutionalized terror.

Nor should it be forgotten that in the latter part of the Twentieth Century, inmates of Alcatraz - America's "Devil's Island" - began to echo similar stories of the Rock that were similar to those painted by Flag for the bagne. Behave and you got along. True, up to the 1980's you would have some former inmates who spoke of brutality, beatings of prisoners in solitary, and the like. But in all cases they were speaking of stories they had heard, not what they saw or knew for fact. First hand accounts spoke of brutality in the sense of boredom, being forced to do routine jobs, eat at regimented times (although the food, everyone agreed, was excellent), and having more or less public toilet in your cell. In other words, they were in a maximum security prison.

All in all the accounts show that the men were treated professionally by the administration. Even one of the ealiest prisoners, Charley Berta, a mail robber who was on Alcatraz from the beginning in 1932 until his release in 1949, said Alcatraz was the best place to serve time. With a cell to yourself, you had far less danger of inmate violence. Prisoners were treated the same and so you had no inmate pecking order so common in other prisons. "There was no hustling," Charley added.

Leon "Whitey" Thompson, also spoke of the routine as the worst part. Day in day out, it was the same. On the other hand he admitted Alcatraz is what got him turned around. And both Whitey and Charley stated unambiguously that the tales of brutality and sadism were fiction. Whitey found it funny that in the movies the guards were the bad guys, and the prisoners the good guys. "We were the bad guys," he said.

But as with all memoirs written by convicted and unrepentant felons (Flag never regretted his life of crime), there is a slight nagging question regarding how much Flag might be stretching things, particularly regarding his artistic ability. The book includes samples of Flag's art where he painted scenes from the bagne. They look like what you might see from an amateur of ability who took up painting to while away the hours. Yes, they were rendered under less than ideal conditions using non-professional equipment. But are they what we expect from a man who claims he could draw recognizable caricatures with a mop on a floor and was able to forge to absolute perfection a Renaissance masterpiece? Hm.

Return to Devil's Island, http://digital.library.umsystem.edu/cgi/i/image/image-idx?page=index;c=devilic. The University of Missouri-Columbia has 24 of Flag's paintings and you can view them at this site. It also has some photos of Flag, including one in his studio. There are some drawings on the wall in the background which do show Flag's artistic ability and training. But still you wonder if he could do the forgeries as facilely as he claimed.

"Devil's Island", Life Magazine, July 12, 1939, pp. 65 - 71. A contemporary look at the then functioning - quote - "Devil's Island" - unquote - during Flag's time which also corresponded to the time the most famous inmate, Henri Charriere or Papillion, was there. The numbers quoted confirm what fiddling with numbers suggests - that perhaps 20 - 25 % of the men were dying each year or at least disappearing. Somewhat hypocritically (given some of the prisons in the United States at the time), the article adopts a rather fatuous and holier-than-thou tone. On the other hand, the gist of the article confirms pretty much what Flag said. Obey the rules, and you could get along. Cause trouble, and you probably wouldn't last too long.

There was also support of the point made in Papillon Épinglé about Papillon's "escape" from the hospital by knocking out the guards. The article confirms that striking a guard was an extremely serious offense and did indeed carry the death penalty. So the story that Henri told how he escaped by smacking the guards on the head and was so eloquent that the judges on the tribunal rendered a well-just-don't-do-it-again-Papi judgement has to be bogus.

There is, by they way, a photograph of Flag painting a picture and it mentions his stealing a painting and substituting a copy he made himself. But if you look at the painting you once more have to ask was Flag so good to pull that off? It doesn't look like it, and we have to remember that what really landed Flag in the slammer was counterfeiting money.

Dry Guillotine, Rene Belbenoit, Dutton (1938). The classic account of life on - quote - "Devil's Island" - unquote. There were times Rene had cushy jobs, too.

Papillon, Henri Charrière, Laffont (1969, Eng. Ed., Morrow, 1970). Often taken as a true account of Henri's life, it is really a fictionalization and adventure tale. A good book, yes, but not literally factual.

Papillon Épinglé, Gérard de Villiers, Presse de la Cité (1970). The famous debunking of Papillon, it's limited circulation among English speakers has limited it's effectiveness among les anglais. Gérard provides considerable information about the regulations of the bagne and particular of the reclusion on St.Joseph. Henri, we learn, really stretched it.

Devil's Island: Colony of the Damned, Alexander Miles, Ten Speed Press (1988). Probably the best general account of the whole Guiana penitentiary system for English readers. Alex avoids sensationalism, but the bagne still does not come off as a nice place even to visit. It was, after all, a prison located in a tropical jungle.

For those who want to compare "Devil's Island" with America's system of rehabilitation in the same era, there are a number of books to check out. A few worth reading are:

Scottsboro Boy, Haywood Patterson and Earl Conrad. Doubleday (1950). The first hand account of Haywood Patterson. Compare Haywood's description of life in the southern prisons to that described by inmates of "Devil's Island".

The Land Where the Blues Began, Alan Lomax, Pantheon (1993). The story of Alan's folk collecting largely after World War II with his accounts of going into the southern prisons. There's also information on the levee camps along the Mississippi. Better than the jungle camps in Guiana? As Big Jake would have said, "Not hardly."

The Folk Songs of North America, Alan Lomax, Doublday (1960). The section on work songs includes details on the southern prisons, including the convict mines. The scenes in the convict mines in many ways, Alan says, rivaled those of German concentration camps.

Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice, David M. Oshinsk, The Free Press, (1996). An excellent book about the Parchman Mississippi prison in particular and the southern penitentiary system in general. Considerable information about the convict leasing system. We even learn that black children as young as twelve would be arrested on vague trumped up charges like vagrancy or loitering, given exorbitant fines, and unable to pay, sent to prison to "work out" their fine. You don't read about this in your middle school civics classes, but we should.