Water Color and Fresco

(With a Bit about Michelangelo, the Sistine Chapel, Leonardo da Vinci, Bronze Casting, and College Professors Thrown in)

Watercolor Paintings

Watercolor is undoubtedly the oldest painting genre in the world and may have been discovered when some Australopithecine accidentally tripped and fell into a mud puddle. Still, watercolor as we know it goes back only a wink of the eye compared to all of human history - a measly 35,000 years - and seems to have started with what early anthropologists called Cro-Magnon men and women when they began to paint pictures on the walls of their homes.

Today watercolor paints generally have some kind of binder - usually the solidified sap of the acacia tree known as gum arabic - to help them stick to the paper and improve pigment dispersion, flow, and consistency. But the earliest watercolors were simply the colors ground up in water. That was good enough for painting on wet plaster walls. Such buon fresco paintings - or more often just called frescoes - were being created at least as early as the Minoan Civilization (between 3500 to 1500 BC). Fresco later became the home decoration of choice in the Roman Empire and the art reached its pinnacle in the Italian Renaissance.

Studies for Fresco?

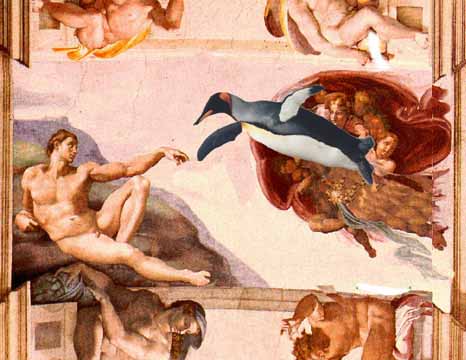

In the CooperToons effort to combat ignorance and superstition it has to be pointed out there was nothing miraculous about a sculptor who had never painted before single handedly creating the fresco masterpieces in the Sistine Chapel. That's because Michelangelo Buonarroti was not a sculptor who had never painted before and single handedly created the fresco masterpieces of the Sistine Chapel. In fact, as a young man Michelangelo had worked in the studio of Dominico Ghirlandio who was the greatest fresco painter of his age. Michelangelo could draw even better than Leonardo da Vinci, and he made paintings for private individuals as well as popes. One of his customers was a baker who commissioned the famous Doni Tondo, which you can see if you click here. This picture was painted before the work on the Sistine ceiling and is clearly the work of an artist with considerable painting experience - and talent.

The idea that Michelangelo did not paint is largely because people take the movie, the Agony and the Ecstasy, to be accurate biography, not a motion picture based on a historical novel with invented dialogues and scenes. We see Charlton Heston was carving a bunch of stone statues when Rex Harrison asked him to paint the Sistine Chapel. Chuck yelled at Rex that he is a sculptor, not a painter, and, His Holiness should get someone who specializes in painting, maybe Raphael of Urbino. Rex, of course, was the Pope and so Chuck had to paint the Sistine Chapel.

The truth is that when Pope Julius II called Michelangelo to paint the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo was working on another painting. The mayor of Florence, Piero Soderini, had hired Michelangelo to paint, yes, a fresco on the wall of the Palazzo della Signoria (now the Palazzo Vecchio), which was the town hall of Florence. The painting was to depict the Battle of Cascina where a (false) alarm had been raised while the soldiers were gamboling about in the river in their all-together. If nothing else, the commission gave Michelanglo the opportunity to paint a bunch of naked guys scrambling around in panic.

When he was called to Rome, Michelangelo had only gotten as far as drawing the cartoon. Before the nineteenth century, the word "cartoon" referred to the preparatory drawing for a painting, particularly the full-size drawing that would be transferred to the surface. When the final design was approved, the cartoon was cut into smaller sections if necessary, and needle-holes pricked along the lines. You then placed the cartoon section against the wall, took charcoal in a bag of loosely woven cloth, and pounced the bag along the lines. The charcoal would poof through the holes onto the wall, leaving an outline.

An alternative method - preferred by Michelangelo - was just to take a knife and cut through the lines leaving the scratched outline on the plaster. The artists then added the colors.

Then as now a Pope trumps a mayor, and Piero never got his fresco. In fact, we don't even have Michelangelo's original drawing, Only a small copy by Bastiano da Sangallo remains.

Ironically there was a double whammy for Piero. When he hired Michelangelo to paint the Battle of Cascina, he had also hired the famous Leonardo da Vinci to paint the Battle of Anghari on a neighboring wall.

Now Leonardo and Michelangelo, although they were acquainted, didn't like each other. Each took swipes at the other. Leonardo once wrote how the sculptor's work:

... is less intellectual than painting and that many wonderful aspects of nature escape him. Practicing myself sculpture as well as painting and doing both the one and the other with the same skill, it seems to me that without suspicious of bias I can judge which of the two is more intellectual, the more difficult, the more perfect.

For the sculptor in producing his work makes a manual effort. This demands a wholly mechanical exercise that is often accompanied by much sweat, and this combines with the dust and turns into a crust of dirt. His face is covered with this paste, and he is powdered with marble dust like a baker. He is covered with tiny chips as if it had snowed on him. His lodgings are dirty and filled with stone splinters and dust.

In the case of the painters just the opposite occurs. He sits at great ease in front of his work, well-dressed, moving a light brush with agreeable colors. He often has himself accompanied with music which he may hear with great pleasure undisturbed by the pounding of hammers or other noises.

Possibly prompted by seeing the cartoon of the Battle of Cascina Leonardo also snorted that:

Many, to seem great draftsmen, draw their figures to look like wood, devoid of grace, so that you would think you were looking at a sack of walnuts rather than the human form.

For his part, Michelangelo didn't think much of Leonardo's art either - or at least not much of Leonardo. A story of a personal encounter of the two men is from a manuscript known as Il Codice dell'Anonimo Gaddiano, which simply means it's an anonymous manuscript owned by the Gaddiano family.

Often told in various biographies of Leonardo and Michelangelo, the story is that Leonardo and two students, one of whom was Giacomo Caprotti (known as Salai, the "Little Devil"), were once walking down a street in Florence. A group of men who had been reading Dante's Divine Comedy asked Leonardo to explain a passage. Just then Michelangelo came walking by. Stumped for an interpretation Leonardo said they should ask Michelangelo who everyone knew to be an expert on Dante. Rather than taking the request as a compliment, Michelangelo saw it as a sneer and replied:

Explain it yourself - you who made a horse to cast in bronze, were unable to cast it, and for shame abandoned it.

As he walked away Michelangelo couldn't resist making a parting shot, "And those stupid Milanese thought you knew what you were doing!"

Michelangelo's rather snooty remarks were referring to the time when Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, commissioned Leonardo to create a bronze equestrian monument of the Duke's father. Leonardo managed to make the full-size model in clay - the first step in making a bronze statue - but never made the final bronze. This, though, wasn't really Leonardo's fault. The Duke had been fighting a lot of wars - not very successfully - and he needed all the bronze to make cannons.

In the end Piero got neither the Battle of Cascina or the Battle of Anghari. Leonardo, whose glacial pace of painting was not suited to fresco, decided to paint the wall using oils. He would dry the paint by hauling pots of burning wood alongside the picture. Rather than dry the oil, the heat made the paints run, and Leonardo - as with a number of his projects - just gave up. He eventually went back to Milan and later moved to France where he died in 1519. Michelangelo, as we said, was called to Rome.

A word of caution about listening to experts. There was an art historian from a major university giving a lecture on Leonardo. But when he started talking about fresco painting he said you painted with egg tempera. Tempera is a water soluble paint made from pigments ground in the yolk of an egg. Yes, the yolk, not the white. The yellow of the yolk has minimal effect on the color.

Tempera was used before the advent of oil painting. Traditionally, you painted tempera on dry surfaces, usually wood panels coated with a mixture of glue and gypsum which had not been heated to make Plaster of Paris. Some recipes called for using powdered limestone. But whatever the actual surface, if you wanted a picture to hang on a wall in 1400, you usually got a tempera painting. Tempera is probably best thought of as the medieval version of acrylic. It can be thinned with water and dries rapidly to a hard smooth surface with bright colors.

It is true that after the painting was finished sometimes a fresco artist wanted some finer details than could be achieved by painting watercolor onto the wet plaster. Such details you would add with tempera within a couple of days. However for making such additions a secco (as it was called), the amount of egg was less than what was used for standard tempera. But the majority of a fresco was painted in straight watercolor, not tempera.

Not to be overly critical, but the same professor also made a bit of a faux pas when talking about what you would have to do to cast Leonardo's horse statue in bronze. He said you make the clay model - like Leonardo did - and then coat it in wax. You then make a mold (also out of clay) around the wax covered model leaving holes as vents to prevent forming air pockets. Then you pour the bronze into the mold. The molten bronze burns out the wax leaving the bronze statue. You remove the bronze and you have your horse.

This procedure as described has some superficial resemblance to the lost wax process but would actually produce a fiasco at best and burn down your studio at worst. First you don't coat the finished model with wax and make a mold. All that would do is make a mold of the wax coat. Why spend a lot of time sculpting the model and then cover up the surface and its detail?

And you would not pour the bronze into a wax filled mold. That would set fire to the wax, producing smoke which would contaminate the metal. It would also produce expanding gases that at best would leave gaps in the cast or more likely blow the mold apart. And if the mold was cold enough to hold wax, it would be cold enough to freeze the bronze before it could fill the mold. As we said, the procedure described would be a fiasco.

What you would really do in the lost wax process is make a mold directly from the model. Before the invention of special self-releasing and flexible silicone and polyurethane rubbers, the molds were made out of plaster. Because the molds were rigid, they would be fashioned in a number of pieces that would fit together like a 3D jigsaw puzzle.

First you would decide where to place the dividing lines on the model so that the separate pieces of the mold would not get stuck in undercuts. You then coat the model with a thin film of a mold release. In Leonardo's day they used vegetable oil diluted in an organic solvent so you would get a uniform coat of the vegetable oil over the surface of the model and still have it thin enough to preserve the fine details. Today you use special silicone sprays.

Next you create walls - shims - along selected dividing lines. The shims are sometimes flat pieces of metal or they can be made of clay. You don't put shims on all the lines at once, but only the lines where you're making the actual piece. The shims are also coated with mold release, and in fact, you usually put the shims in place before adding the mold release to the statue.

Then you add thin watery plaster to the surface of the section you're working on. Watery plaster makes sure the mold preserves the detail. When the plaster sets up but is not completely dry you add another thin layer of plaster and then successive layers of thicker plaster. Again you let each plaster layer set up but not dry out. That way the top layers merge with the previous one and so you don't have the layers separate and pull apart.

When the first parts of the mold have hardened - at least a few hours - you remove the shims but leave the mold pieces in place. You then add the release agent to the sides of the mold where the shim was, and add new shims where needed. After a new dose of mold release, you add plaster to the new section and make another piece. You continue the process until pieces have been made for the whole model.

The pieces are removed from the model when dry - if they are too wet they can be crumbly. But if the mold release works, you can remove the pieces without loosing the detail or breaking the pieces. Some complex statues can easily have over 100 separate parts of the piece mold.

Now we come to the wax part.

The mold you've just made is now used to produce a wax copy of your clay model. So once you have all the parts of the piece mold, you again add release agent to the inside surface of the mold.

Now you add the wax. But you only coat the inside of the molds to about 3/16". This is to keep the final bronze statue from being too thick.

Of course, you have to let the wax harden. Then you can remove the wax cast from the mold. If done properly the wax will preserve the shape and details of that part of the original model - and on the outside surface - which is exactly what you want.

By now you have relatively thin copies of the sections of the original statue. If you then put everything back together - relatively easy with wax - you will end up with an exact, but hollow, copy of your original model. Usually, though, you only assemble some of the parts as large statues are always cast as separate pieces.

The story was that Leonardo was going to cast the horse in one piece rather than as separate parts which is the norm. This plan would certainly have been a disaster and we know that Ludovico, Leonardo's boss, asked the Florentine ambassador, Piero Alamanni, to write to Lorenzo de Medici for help. Ludovico said that he had asked Leonardo to make the model, but that he needed a couple of skilled bronze foundrymen to do the casting since he was not sure Leonardo would succeed. Leonardo had by then developed a reputation for being something of a piddler and starting things that he never finished.

But once you have the wax parts in hand, you now have to make more molds - but molds made to surround the wax casts. In Leonardo's time these were made out of a clay that would stand up to the heat of the molten bronze. Today they are made from special alumina silicate sands bound with a ceramic binder. To see examples of the (modern) process click here for a brief discussion of making the shells with a more detailed telling if you click here. To see the actual casting of the bronze, you can click here.

Of course, the molds have to be made with vents and openings properly placed. But when the molds have dried, now you can burn out the wax. True a lot of the wax melts and runs out, but the burning of residual wax makes sure the interior of your mold is clean.

Then before the molds can cool - they have to be at least 1600 degrees Fahrenheit - you pour in the bronze. The bronze fills the mold and cools. Then you wait - usually at least 24 hours, but sometimes longer, and then whack away the mold. You end up with a bronze copy of your wax parts. Assemble the pieces (Leonardo would have used rivets, modern foundries use welding), and hey, presto!, you have a hollow bronze horse.

Alternatively, Leonardo could have used sand casting. We won't go into details for this exacting but less expensive process, but you can understand why there are more watercolorists than bronze casters.

Fresco painting is done on plaster which has set but is still wet. The plaster is laid down as at least two layers, one with plaster and coarse sand (called the arriccio) and the other in plaster with fine sand (the intanaco). You only put on enough plaster for a day's work, and the area is called a giornata, which means a day's work (the Italians are very commonsensical people). Any excess plaster has to be cut away before starting the next giornata.

Watercolor itself is not a particularly forgiving medium and fresco painting even less so. Rather than try to correct a mistake, it's simpler just to cut away the plaster and redo the whole giornata. Either that (as often happens) you just leave the mistake and hope no one will notice.

Fresco Mistakes

You hope no one will notice.

So fresco painting requires considerable preparation and planning. You need to know exactly what you want to paint down to the different tones and shading. It's also a group effort with some on the team making and applying the plaster, others transferring the drawing, and then other artists adding the color. With the decline of the large workshops of the Renaissance, the use of fresco for murals also declined.

Michelangelo was an excellent painter before he started on the Sistine Chapel, but he did not have a lot of personal experience in fresco. So he hired five experts in the medium to help. Like all successful Renaissance artists, Michelangelo was no solitary artist but at times had as many as a hundred contract artists working on a single project.

Critical to fresco's durability is the proper surface. The plaster is created from lime which is what you get when you heat limestone. The heat drives off carbon dioxide from the calcium carbonate leaving calcium oxide.

CaCO3 → CaO + CO2

... and when you add water you get calcium hydroxide or slaked lime:

CaO + H2O → Ca(OH)2

The important point is when you start painting, pigment is carried into the wet plaster. The colors don't just lay on the surface.

Then when the excess water evaporates, the plaster dries. But also the calcium hydroxide begins to absorb (yes, ABsorbs) carbon dioxide.

Ca(OH)2 + CO2 → CaCO3 + H2O

So with enough time, the surface of the wall returns to limestone with the pigment trapped beneath the surface. So you have a strong surface with the pigment as part of the wall.

So why, you ask, do old frescos often look so bad?

Well, of course, much of the problem is physical damage. If some rich guy in the 1700's wanted a fresco from Pompeii, he'd send in his flunkies to cut it out of the wall. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn't and a lot of frescoes ended up broken on the floors.

Alas, modern air pollutants - particularly sulfur dioxide together with air - also react with walls and cause deterioration. Calcium carbonate - which should last for millions of years - will change to calcium sulfate which we know as Plaster of Paris.

2CaCO3 + 2SO2 + O2 → 2CaSO4 + 2CO2

A greater problem is that ubiquitous pollutant - water. Calcium sulfate has some water solubility - particularly when there is also acid around - and so rain and moisture will etch the walls.

It can even be worse if moisture accumulates in the wall behind the painting. Then the surface can become detached and the painting falls apart. This was a real problem in 1966 when the Arno River flooded and covered some of the old frescoes. The frescoes had to be be stabilized on the walls and this was done by taking them down.

Yes, the conservators took the frescoes down. They did this by covering the painting with a glue that would not damage the painting and later could be removed. They then placed a cloth over the painting and let the glue dry. Next the conservators cut along the border of the cloth and slowly peeled off the painting. Back in the museum they attached the painting to a large metal plate and removed the cloth and the glue. After retouching areas where color had fallen away - called lacunae - the metal-backed fresco was put back on the wall.

Restoration is a touchy issue, and we can say with some accuracy that the field is divided into the anti- and pro-Restorers. The anti-Restorers think restoration goobers up the painting and what you get isn't what the original artist actually painted. The pro-Restorers, although acknowledging that some details can be lost in conservation (the term they prefer), say that the artists did not intend the paintings to look like dim soot and dirt encrusted images. Instead as oil and tempera paintings attest, Renaissance artists originally painted with the bright colors.

A problem in paintings is that varnish or wax is sometime added to protect the paintings. But the coatings themselves deteriorate and darken and so you have to remove the varnish without hurting the picture. Sometimes you can't do this. In one famous painting, the Adoration of the Magi, which Leonardo started but never finished, he didn't let the painting dry completely, and the varnish actually seeped into the paintings. So with this painting you can't remove the varnish without removing the painting.

After World War II, modern restoration method were developed using new protective polymers, some of which indeed goobered up the pictures. So today conservators find themselves trying to undo the earlier restoration work by using high technology such as lasers and nano chemistry. So far what they've done looks pretty impressive and doesn't appear to be goobering up the un-goobering.

References

Bright and Beautiful Flowers in Watercolor, Jean Spicer North Light Books, 2004.

Fresco Painting: It's Art and Technique, James Ward, Chapman and Hall London, 1909. Reprints from various publishers are available.

Leonardo on Art and the Artist, Leonardo da Vinci, Orion Press, 1961 (Reprint, 2002, Dover Publications)

Michelangelo: A Biography, George Bull, St. Martin's Press, 1998.

Leonardo da Vinci: Flights of the Mind, Charles Nicholl, Penguin Books, 2005.

"Modern Chemistry Techniques Save Ancient Art", Rachel Brazil,Chemstry World, Royal Society of Chemistry, June 23-25, 2014