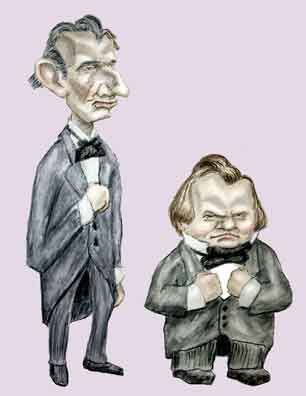

Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas

(And the Time When Debates Were Debates)

Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas

(Psst! That's Lincoln and the Right.

Sadly today's so-called political debates have just about hit the nadir and are now nothing more than Q & A PR WebFests hosted by stylishly coiffured journalists fantasizing how they will be the next Bob Woodward. Worse, the "issues" discussed, rather than covering what the candidate intends to do once they get in office, are more likely to be about how choices of lapel pins reflect on a person's patriotism. But when Abraham Lincoln debated Stephen Douglas in 1858, those were debates, by God, and the candidates debated the issues.

Contrary to (perhaps) popular belief, the Lincoln-Douglas Debates did not take place during a campaign for the Presidency. Yes, two years later Honest Abe and the Little Giant would contend for the country's top spot (and Douglas would hold Lincoln's hat at the inauguration), but in 1858, Lincoln was running against Douglas for the US Senate. All the more odd - to modern understanding - is US Senators were not elected by the voters. Instead, the state legislators voted on the Senate seats. This was changed only in 1913 by the 17th Amendment to the Constitution. So what was the point of debating at all?

Well, the US Senators may not have been directly elected by the voters, but the state legislators were. So vote for someone your constitutents didn't like, and you could kiss your seat - legislatively speaking, that is - good-by.

The format of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates seems incredible given the fifteen second sound-byte journalism we enjoy today. The first candidate would talk about his views and politics for an hour. Yes, that's an hour. The second would get up and talk an hour and a half. Yes, that's an hour and a half. Then the first speaker would get up and finish with a half hour rejoinder. So you had three hours of speeches, delivered completely outdoors and sometimes in sweltering heat. The crowds loved them and cries of "Good! Good!", "That's right!", and "Hit him again!" peppered the speeches.

What really distinguished these debates - seven sessions spread out over a period of two months - was the words were written down verbatim in shorthand and transcribed for immediate publication (which meant in two to three days). That was high technology of the time and these debates really marked beginning of what might be thought of journalistic journalism.

Papers in those days were unabashedly partisan. The pro-Lincoln (and Republican) Chicago Press and Tribune would inevitably report that thunderous cheers and applause greeted Lincoln before and after the debates and smirkingly tell how Douglas looked chagrined and dismayed at being bested and at his lukewarm reception. On the other hand, the Chicago Daily Times (pro-Douglas and Democratic) reported the opposite, how Douglas's speeches met unrestrained approbation and enthusiasm while the tall, gangly, and ungrammatical Lincoln clearly showed his irritation when Douglas's amazing oratory left his own position worsted.

Naturally each paper supplied their own stenographers. The Times sent Henry Binmore and James Sheridan and the Press and Tribune first sent Horace White and later the twenty-four year old Robert Hitt. Hitt was Lincoln's favorite ("Ain't Hitt here?" Lincoln once queried, "Where is he?"), and Robert had been the official stenographer for the Illinois legislature. The presence of two partisan recorders provided something of a check on a possible temptation to gussy up the words of the favorite candidate and make unfortunate "errors" when recording the speech of the opposition.

That didn't mean that an editor, though, didn't try to help his favorite candidate out. Since the record had to be transcribed into longhand and then set into type, misstatements, mispronunciations, and mid-sentence changes in thoughts could be easily "corrected". Douglas' also had a tendency to use epithets that even then weren't considered quite proper among the polite. So you had the times when Douglas was actually censored by his own papers.

All in all, the departure from a stump speech format gave Douglas the advantage. For all his ability as a writer and skill in delivering prepared texts, Lincoln could be a horrible impromptu speaker. Both candidates, though, sometimes flubbed what was intended to be eloquent oratory, and some of Lincoln's more memorable quotations were at least in part due to the polishing of a sympathetic editor.

For the opposition, though, the editors tended to leave bad enough alone and just print the text as transcribed. Oddly enough, then, it was the readers of the Democratic papers that read the unedited text of Lincoln, and the Republican readers got the verbatim transcript of Douglas. It was only in the latter part of the Twentieth Century that the unexpurgated transcripts were put together in one volume.

But given the circumstances, conditions, and at times, pure chaos of the debates (once Lincoln got so ticked off at what Douglas said he jumped up and had to be forcibly pulled back to his seat), the different versions of the texts agree surprisingly well. Above all, you have to admire the eloquence and sheer stamina of both men.

What is more of a shock is the content of the speeches. It is certainly disconcerting to read that even at that early time in our history, a major political candidate could stand up in front of thousands of men, women, and children and state flat out that he was not in favor of equality among the races, did not believe in granting the vote for minorities, and was in favor - yes, in favor - of maintaining the superior position of the white race above the black.

And that was Lincoln!

But for now our presidential campaigns will continue with years and decades of media blitz, negative ads, and out and out smear tactics to the point we'll have absolutely no idea what a candidate will do once in office. But maybe that's the way they want it. Which leaves only one question.

Parliamentary system, anyone?

References

"The Lincoln-Douglas Debates: The First Complete, Unexpurgated Text", Harold Holzer, Ed., HarperCollins (1993), new edition, Fordham University Press (2004). By using the texts of the candidate printed in the opposition papers, Harold has gotten as close as possible to giving us the words actually spoken. Perhaps the biggest surprise is not that we see some differences in the earlier approved texts and those in the opposition papers, but how similar they are. For the most part both candidates spoke for an hour and a half clearly and grammatically.

Versions of the debates are online. The National Park Service has a nice website showing the towns where the speeches were made, dates, and the transcripts. But dang it, they keep changing the URL! As of this revision it is now at http://www.nps.gov/liho/historyculture/debates.htm. But if you click on the link and it's not there, just do a search on "Lincoln Douglas Debates National Park Service" or something like that.