Grigóriy Raspútin

Старейшина Чрезвычайный

Grigóriy Raspútin

Старейшина Чрезвычайный

The Reabilitatsiya of Grigóriy Raspútin

Grigóriy Raspútin - or at least his reputation - seems to have undergone quite the Renaissance since the fall of the Soviet Union. The man who was once universally dubbed a charlatanistic con-man, swindler, and lecherous vulgarian - not to mention being a возбужденный сволочь - has now emerged as a "mystic" who "must have had undoubted powers of healing" as well as the "gift of prophecy".

As for his cavorting with wild women, boozing, and getting rub downs in establishments meant for male relaxation, the usual rationale is that Grigóriy was simply obeying the teachings of his religious order. Before we can overcome sin, he said, we must experience sin. Only then can we reach the highest state as a true Witness of Faith.

But Grigóriy's friends say all the stories were created by Grigóriy's enemies. The truth, say the members of the Raspútin Fan Club, is he was a deeply religious and fervent monk who was maligned and slandered by the later Communist regimes to discredit both the Romanov family and the Orthodox Catholic Church - which has granted the Romanovs sainthood as страстотéрпец (strastotérpets) or "passion-bearers". Grigóriy, we read, was a loving family man. He did not drink, smoke, or indulge in improper behavior, and photographs of him surrounded by celebrating ladies are fabricated.

He was also a man of superhuman powers, a true mystic healer and prophet. That he had the power to heal can't be doubted given the numerous eyewitness accounts that affirm how his intervention saved the life of the son of Tsar Nicholas II. His prophetic powers were also remarkable as he predicted the tragic end of the Romanov dynasty with uncanny accuracy.

And finally we must remember that Grigóriy Raspútin was the man whom no one could kill. Only the forces of nature and the icy waters of the Neva River could do that.

There is one thing, though, that everyone can agree with. Even more than a century after his death, Grigóriy Raspútin still has the ability to win friends and influence people. At least people keep paying good money to buy books about him.

The Rodoslovnaya of Raspútin

We suppose, of course, the best place to start is at the beginning. So let's look at Grigóriy's early life 'ere we delve into the more controversial topics.

Grigóriy Efimovich Raspútin, we read, was born in the Siberian town of Pokrovsky (now more often transliterated as Pokrovskoe) on January 10, 1869. The trouble is you'll find alternate dates ranging from 1860 to 1873. Grigóriy himself said he was 52 in 1915 so that would make the year 1863 or possibly 1862.

On the other hand, a recent biographer stated that Grigóriy was born on January 9, 1869. But he was baptized on January 10. January 10 was the day of Saint Grigóriy of Nyssa, and keeping with the custom, the kid was named after the saint.

There is a final monkey wrench thrown into the historical record, though. His daughter Maria stated flat out that her dad was born on January 23, 1871 - coincident with the appearance of a comet. But whatever date you pick, that Grigóriy was born at some time isn't to be doubted.

Although Grigóriy is often called a "Siberian peasant", the choice of words is both true and misleading. It's true because it is true. It's false because the word "peasant" in Siberia doesn't really match with what most people think of as a peasant.

Today we learn that the Russian peasants were serfs tied to the land, a status that changed only after the Communist Revolution. And Siberia was a horrible place, suitable only as the future home of the Gulag.

However, the real Siberia is a land rich in natural resources. True, the winters can get cold as ад, but the region has always supported thriving agricultural communities. And despite what at least one American textbook taught, Russian serfdom was ended well before the Commies took over. In fact, way back in 1861 Tsar Alexander II decreed that all serfs were to be free and they were to be granted their own land. In Siberia the peasants also operated largely independently of the landed aristocracy - something not true for a lot of former serfs.

So "prosperous small farmer" is a better way to describe Grigóriy's dad whose name was Efim - there is a pun there - and his mom was the former Anna Parshukova. Efim - in Cyrillic this is spelled Ефим and is now often transliterated Yefim - was literate and we hear that each night he read the Bible to his family - between tokes of the remarkably strong Russian vodka, of course.

Although the Raspútins were pretty well off for the place and time, life in Siberia was no bed of straw. When Grigóriy was young, his older sister, Maria, drowned in one of the region's many rivers. But it was the death of his brother Dmitri that is often cited as a turning point in Grigóriy's personality. According to one account, the two boys had been swimming but were swept away by the current. Although a passer-by managed to pull them to shore, both came down with pneumonia. Grigóriy recovered but Dmitry died.

By the time he was in his teens Grigóriy had become what we call a "handful". Fueled by alcohol and hormones, he would sometimes get a cart and whip up the horses as he dashed around town shouting imprecations at everyone he saw. If he was walking around town and saw a young lady who took his fancy, he would simply reach out and try to undo her bluzka right there on the street.

Now we do have to admit that the stories of Grigóriy's childhood come only after he was grown and had made lots of aristocratic enemies. That Grigóriy did develop a fondness for the ladies and the bottle is hard to deny. In fact, it's quite typical for many young men. Grigóriy also smoked - again a common habit for the time.

Bolstering the claim Grigóriy really did have a bad-boy persona is the story that he picked up the moniker Raspútin from his lifestyle and that his real last name was Novykh. Raspútin, we hear, is related to the word распутник (rasputnik) which means "libertine" or "reprobate" with the added connotation of being a wild man.

Actually Grigóriy got his name from his dad, and Raspútin was their bonafide family name. Folk etymology - often discourteously called "spook" etymology - is notoriously unreliable, and there are similar sounding words that have nothing to do with debauchery. Rasputa means "crossroads" and raspustista refers to the wet muddy season of the Siberian spring. All in all, the surname has no meaningful connotations to a rouée character.

That Grigóriy liked to carouse, though, isn't to be doubted. His daughter Maria remembers her dad liked to visit gypsy camps to drink and dance. He was, though, a bit remorseful that all that partying hadn't been good for his health.

In the 1880's Grigóriy met a young village lass named Praskovaya Dubrovina who was his senior by a few years. Again the story is she enjoyed his company, but she did not let him have his way. Perhaps it was her playing hard to get that prompted Grigóriy to propose marriage, a proposal Praskovaya accepted.

Grigóriy and Praskovaya probably got married around 1886. If he was born in 1863, he would have been 23 years old and Praskovaya about 26. This is a bit old for a marriage at that time and place. If 1869 was the year, then their ages would be 17 and 20 - more typical. So again we give the 1869 birthdate the nod.

Career Change

What transformed Grigóriy from either a raffish ne'er-do-well or a typical Siberian peasant into a holy man and mystic depends on who tells the story. One tale is that he got into trouble with the law. Oh, it was mostly minor destruction of property and petty theft - stealing some horses and yanking up some wooden stakes from a neighbor's fence.

But there were tales of more serious offenses where contrary to law and decency Grigóriy forced his affections on unwilling local lasses. Whatever the offense, we learn he was banished.

Of course, he couldn't be banished to Siberia - he was already there. So the question was what to do with him. Grigóriy, though, solved the problem by requesting that he be sent to the monastery at Verkhotury about 300 miles away. In three months, he was back in Pokrovsky.

Suddenly Grigóriy had become enthusiastic about religion. Historians aren't quite sure what was it that grabbed his attention. The stories make it seem like he was a хлыст (khlyst).

But what exactly was a khlyst?

Like many fringe sects we don't know exactly. But the rumors were they had wild and crazy rituals that sometimes got out of hand and turned into orgies. Supposedly they also liked to whip themselves and their basic belief was that you had to experience sin to overcome sin.

Grigóriy adapted this philosophy with élan. Of course he also tried to be a better person. We hear he gave up tobacco and alcohol, the latter a remarkably short-lived hiatus. Nor did his religious predilection with the ladies seem to bother Praskovaya who roguishly said her husband had plenty and to spare.

All this, as we said, is one story.

Grigóriy's friends point out that there is no actual records about any conviction for the supposed crimes, even though in the early 1900's some of his enemies tried to dig up some dirt by going to Pokrovsky and riffling through police files. They came away empty-handed, and there is no real evidence Grigóriy was banished. But it does appear he might have been put in the slammer for a couple of days for being snooty to one of the town's officials.

The truth is we don't know when Grigóriy began to wander around as a holy man. It seems he did so gradually. He himself said he made his first holy trip in 1893. But others who knew him remember it was more like 1897.

In much of the 1890's it appears Grigóriy was officially living on the family farm with his dad, mom, and Praskovaya. If he was wandering around, he must have returned home on occasion since between 1897 and 1900 he and Praskovaya had three kids. The #2 kid, Maria, is the one we know most about since she lived well into the 20th century. We'll talk more about Maria later since she's an interesting lady in her own right.

It was in fact Maria who tells us that in his adolescence her dad had begun demonstrating not just mystic healing but psychic powers as well. So he could not only make people feel better, but now he could help the local constabulary locate criminals à la the stories of today's famous "psychic detectives".

Sadly, there is (again) no contemporary evidence for such claims. Maria - whose real name was Matryona - wasn't born until 1898 or possibly 1899 when her dad was about thirty. So Maria had no first hand knowledge of her dad's early exploits.

At this point we need to pause and point out that despite the commonly applied label, Grigóriy was neither a priest nor a monk. He never took religious orders or even any systematic theological studies. In fact, he may have had only minimal literacy and that acquired only in early adulthood.

So why did Grigóriy really embrace the Church? Sure, it could have been a sincere conversion, but his dad, Efim, once grumped that Grigóriy's love of the mystic life began as an excuse to avoid honest work. Efim may have a point since we hear Grigóriy's piety really began when he was plowing the family farm and had a visitation from the Virgin Mary telling him to do something else.

One thing that does seem clear is that while living in Pokrovsky Grigóriy met a young theological student named Melity Zaborovsky, who would later become the head of an Orthodox seminary. Grigóriy talked about his visions and Melity said it was a sign of a religious avocation. That was good enough for Grigóriy, and he started wandering around.

Moving Up

All right. So how did a wandering self-styled lay preacher and small farmer end up being a confidant to one of the last and most powerful absolute rulers in the world? Well, it's not something people do everyday, but it is possible if you have good powers of persuasion and a little bit of luck.

First we'll ask another and more fundamental question. How the heck did Grigóriy make a living wandering around Russia? Shoot, even monks have to eat. And drink.

In our mega-mobile times with its cheap motels and discounted airfares, we forget that the realities of 19th century travel dictated a culture of private hospitality. After your day's trek you simply knocked at the door of the nearest house. There you could find a place to sleep - if not an actual bed - and scrounge a meal. It might not be much - a bowl of ukha and some bread - but it would be enough to send you on your way.

Travelers could also find accommodations at the monasteries that had sprung up over the centuries. Even today some monasteries have special rooms for overnight guests although there is usually a moderate charge. You were particularly welcome if you were on a religious mission which is something Grigóriy claimed.

And there really wasn't anything that remarkable about Grigóriy's wandering around. A number of religions had men living such a vagabond lifestyle. You had the Franciscans in Europe, wandering lamas in Asia, and your circuit preachers in America.

In Russia, they were called старцы (startsy), (sing. старец or starets). Sometimes translated as "healer" or "wandering mystic", the word more literally means "elder".

And it was as a self-styled старец that Grigóriy's soon learned that people really didn't want advice or teachings. Instead, they preferred reinforcement and agreement for what they already believed. All effective speakers are aware you must adapt the talk to the audience, and Grigóriy was, if nothing else, an effective speaker.

There was, though, a curious quality to Grigóriy's modus religionis. He had a real knack for making favorable first impressions but rotten second impressions. So soon his newfound friends - particularly the local priests and politicians - begin to think this wandering sage who had seemed so wise and thoughtful was nothing more than a swindling con-man.

Part of the problem may have simply been resentment that Grigóriy - a religious amateur - attracted a large following from among the people. And by people we mean a good chunk of the ladies. Claims to the contrary, there can be no doubt that most of the photos of Grigóriy posing with a bevy of admiring women are genuine - even of him wading with the ladies in the rivers.

Naturally stories of his boozing, time spent in the bath houses, and his hitting up on the local ladies abounded. One story was that a society matron saw him come out of a bath house with her two daughters in tow. He had obviously been teaching the girls that to overcome sin you must experience it. Noticing their mom, Grigóriy smiled and said, "Now you may feel at peace. The day of salvation has dawned for your daughters."

Now one fundamental principle of historical research is that half-century old second hand memories you heard from your grandfather - even if given in good faith - must be accepted with the proverbial grain of salt. Indeed many of the famous accounts - such as Grigóriy's standing on a balcony and waving to the crowd (but not with his hand) have no first hand sources.

Ultimately we end up with two ways of explaining the hostility that rose against Grigóriy. One explanation, as we said, is that the Church leaders began to resent this lowly peasant who could gain so much influence over their congregations (and particularly the ladies). The establishment disapproval was shared by Russia's political elite who detested this farmer who never washed and you could tell what he ate last week by looking at his beard.

The other explanation is that where there's a lot of smoke, there must be a big fire. That is, the stories are true, and Grigóriy was simply carrying on the tradition of the swindling con artist using religion for his personal wealth and pleasure.

In any case, it appears that in whatever town or village Grigóriy found himself, eventually he would have to pull up stakes and move on. His itinerary is unclear. A very early early article about Grigóriy says he actually made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem (unlikely), and another is that he wandered down to Greece (possible). But we do know that at one point Grigóriy left Siberia altogether and wound up in the metropolitan city of Kazan only 500 miles from Moscow.

Hitting the Big Time

In Kazan, Grigóriy stayed at the home of a well-set businessman named Katkov. Chez Katkov Grigóriy met other substantial citizens including the local government officials and priests. As usual the men were initially impressed with Grigóriy's talk, and among his new admirers was Father Michael who was also a professor at the St. Petersburg Seminary. Invited to St. Petersburg, Grigóriy met - and again impressed - the regional bishop, Father Andrew. In 1903, Grigóriy moved to the city.

It's one thing to beg a room along the road in rural Siberia. But it's something else to become a permanent guest at the homes of high society. In the 19th century the uppercrust never dealt with anyone unless they were formally introduced. So how could Grigóriy just waltz into a major metropolitan area and suddenly end up living in the houses and homes of the most substantial citizens? We'd like to know how Grigóriy pulled that off.

I thought you would, as Captain Mephisto said to Sidney Brand. It's very simple really.

In the 19th century a formal introduction did not necessarily mean a personal introduction. Because of the slow and uncertain communication and travel, custom permitted a now rather quaint and pasée alternative. This was the letter of introduction.

To get a letter of introduction you first had to meet some bigwig. You might have been introduced to that bigwig by a mutual friend or perhaps the bigwig had a bigwig job that entailed him meeting people. Once ushered into his office, it was important not to actually ask for anything specific. Instead, you'd state your general background and and outline your proposed career path. If you made a good impression, you could get your letter of introduction.

Tom with Ben

He made a good impression.

For instance as a young man in London, Thomas Paine was interested in science and philosophy and had attended public lectures on various topics. There you could talk to the lecturers. One of them suggested that Tom pay a call on Benjamin Franklin who was the colonial representative in London.

By actually meeting the lecturer, Tom could say he and Ben had a common acquaintance. That gave Tom the wedge he needed to knock at Benjamin's door. After introducing himself, he said he wanted to go to America. Tom made a good impressions, and Ben - affable and cordial as always - wrote out a nice letter of introduction addressed to his son-in-law Richard Bache who was a substantial businessman in Philadelphia.

Letters of introduction could be sent by post, but this was risky in countries whose mail services were unreliable or non-existent. Or you could trust it to a friend who happened to be going to the city where the intended recipient lived. Finally you could hand the letter over in person. This was the most reliable and safest way of delivery. But however you sent the letter, it was considered the same as a formal introduction.

So when you arrived it would not be as a total stranger. With the letter in hand, the recipient was then under some obligation to his friend and therefore to you. At the least you could expect an invitation to a dinner party or a reception.

With his ability to make favorable first impressions, Grigóriy had no problem scrounging letters of introduction. If the writer ever started to think that Grigóriy was a jerk, it was too late. Grigóriy had moved on.

Letters of introduction would hopefully produce a chain reaction. One dinner or reception produced more invitations to dinners and receptions with even more introductions to more fat cats. Soon there wasn't a party at St. Petersburg worth its champagne and caviar unless Grigóriy was invited.

As usual some of the admirers became former admirers. These anti-Raspútinites who had once held Grigóriy as a wise and perceptive starets began to see a snide and cynical opportunist. And of course, we hear Grigóriy kept up his pursuit of the ladies.

But not everyone flipped their opinions. After all, St. Petersburg was pretty big and were enough of the rich and famous that Grigóriy always had powerful friends. He was put up in a nice apartment where his two daughters Maria and Varvra joined him. His dad, Efim, paid a brief visit, but Praskovaya remained at the family home in Pokrovsky.

It wasn't just the wealthy families with comely daughters and impressionable wives that made St. Petersburg such an ideal base of operations. It was also the home of the Winter Palace, the primary residence of Tsar Nicholas Romanov, his wife Alexandra, and their kids. So it didn't take long before Grigóriy was introduced to friends and relatives of the Tsar and Tsarina themselves.

And We Mean Big

Finally the inevitable happened. On November 1, 1905, Nicholas wrote in his diary: "We became acquainted today with Grigóriy, a man of God from Tobolsk province." Grigóriy must indeed have made a favorable impression since he was soon invited to a private meeting with Nicholas and Alexandra at the Winter Palace. He also met the kids. The girls were pre-teens and Alexei - the only boy - was not yet two.

For all the ease of their lifestyle, the Romanov's had a big worry. Alexei was the only family member who could legally take over since the ruler of Russia had to be male. But it also quickly became evident that Alexei had inherited hemophilia from his great-grandmother, Queen Victoria. What should have been minor bumps and bruises produced intense pain and extended hemorrhaging. The royal physicians warned Alexandra that there was no cure and that the prognosis was not good. Each bleeding episode sent Alexandra into deeper and deeper hysterics.

Drina

It was spontaneous.

Grigóriy, on the other hand, understood perfectly how to handle the distraught mother. Just tell her what she wanted to hear. He assured Alexandra that as Alexei got older he would "grow out" of his illness. At the age twelve, he said the improvement would clearly be evident. And by the time Alexei was an adult, Grigóriy promised the boy would be perfectly normal.

All of this, of course, is absolute and total хуйня́. To this day, although hemophilia can be treated, it has no cure. But in one thing Grigóriy was correct. Eventually Alexei would have no need of any further help.

In the meantime, Alexei had to negotiate his way through childhood. He did his best and the Tsarevich became surprisingly active for someone as protected as he was. There is a film of him tumbling out of a hammock and bounding up without any ill effect. But some bleeding episodes were quite serious and we learn that Grigóriy's - quote - "powers of healing" - unquote - repeatedly snatched the Tsarevitch from the jaws of death.

An Modest Inquiry

All right. Were the stories true?

Grigóriy's fans say absolutely. Remember, we're talking about hemophilia - the dreaded disease where the slightest bump could mean instant death!

Weeeeellllllll, just a minute. There are misconceptions about hemophilia as there are about other diseases. Hemophilia - and the bleeding episodes - can range from mild to moderate to severe. Of course, today people with hemophilia can live perfectly normal lives and with proper consultation with their physicians, even engage in suitable exercise like swimming, badminton, cycling, and walking.

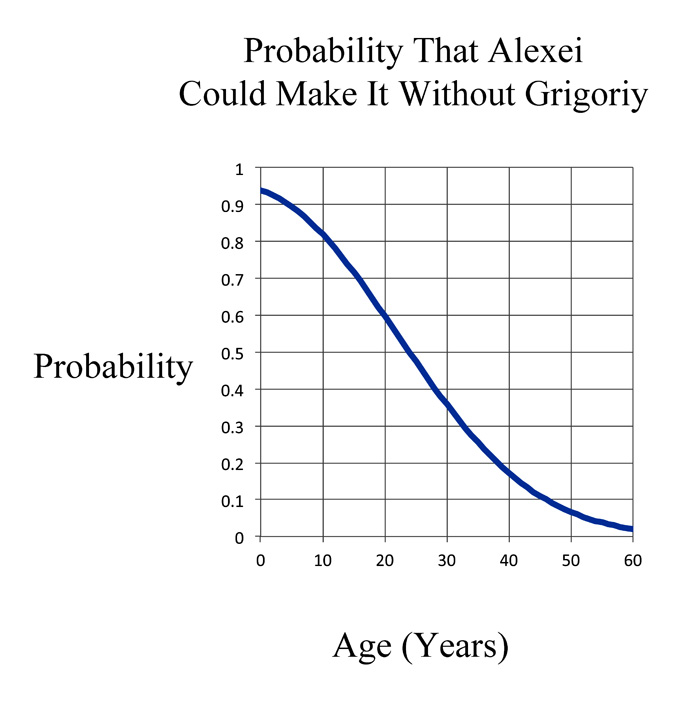

But we're talking about the early 20th century. Back then how likely was it that Alexei would have survived without any miraculous intervention? Put in another way, just what was the life expectancy for a hemophiliac in the early 20th century?

Now if you consult medical articles, you learn it wasn't long. A study done in Sweden found that between 1831 to 1920, the average life expectancy of a hemophiliac was 11 years. Alexei lived longer than that and as we know he didn't die of hemophilia.

So Grigóriy must have helped?

Правильно?

Well, comrades, let's step back a moment. Then as now life expectancy varied on how rich you were. Rich people usually have the best medical care and so live longer. And early 20th century medicine, although rather rudimentary by our standards, was usually better than nothing.

Queen Victoria - Drina to her friends - had nine kids and keeping with the misguided philosophy that families wouldn't wage war against relatives, she sent her chromosomes into almost every royal family of Europe. And somehow, somewhere she picked up the gene for hemophilia. There was no indication that before her, anyone in her family had been afflicted.

That the condition began with Drina raises some eyebrows. We were told on the celebrity quiz and panel show Qi that the odds are 1 in 50,000 that someone will spontaneously develop the transmittable gene for hemophilia. The suggestion was that Drina's mom had been making whoopee behind her royal husband's back and somehow shared genetic material with a hemophiliac. And so Drina herself, although not exhibiting symptoms of the disease, was a "carrier", and her sons had a 50/50 chance of having the disease.

Now there are between 1 and 25,000 and 1 out of 30,000 live male births per year with Hemophilia B - the type of hemophilia in Victoria's family. And about one third of the cases are from the spontaneous mutation of the gene. So the Qi Elves seem to be confusing the probability of someone in the general population having the gene by spontaneous mutations (quite low) with the conditional probability that if you have Hemophilia B then it formed spontaneously - about 1 out of 3. The numbers sort of work out if you futz around with probabilities and make certain assumptions. The Qi Elves may also been thinking about Hemophilia B forming from an acquired immunological response - very low.

The point is that given that Queen Victoria was the first of her family to carry hemophilia, the likelihood the gene arose by spontaneous mutation of the gene is about 30% - well within the bounds of probability. So there is no reason to cast winking leers at Drina's mom.

But as far as the topic at hand, we can look at the verifiable cases of male descendants of Victoria who had the disease. They were born between 1853 and 1914.

Head injury | ||||

fatal even without hemophilia | ||||

Injuries normally minor | ||||

Injuries normally minor |

But note. The life expectancy here is 23 years - 24 for those who did not have Grigóriy helping them out. But either way we are well above the 11 years life expectancy of hemophiliacs of the general population (today of course the life expectancy is much longer). So it does seem that if you had hemophilia and were related to Queen Victoria then you had better odds than your usual Joe and Josephine Blow in the streets.

But there's more. This is a pretty good sample size and is representative of the life expectancy of male hemophiliacs with the best medical care of the time. So we can use fancy pants data analysis to calculate the probability that Alexei could have made to any given age.

In other words, we will calculate how long we could expect Alexei to live even if Grigoriy hadn't been around.

The results may not be what you thought. Without going into the details - you can check textbooks for that - we see that the expectation that a male descendant of Queen Victoria with hemophilia would make it to age 13 - the age Alexei died - was 75%. So we have to conclude Alexei could have easily lived as long as he did without Grigóriy. To prove otherwise we need additional evidence.

But we do have that other evidence, don't we? Aren't there eyewitness accounts that Grigóriy healed the young boy in a manner that all must admit was miraculous?

Well, the things that you're liable to read not in the Bible - as Sportin' Life might have said - ain't necessarily so. A review of the - quote - "eyewitness accounts" - unquote - of Rasputin's miracles vary considerably with the teller. For instance, an episode may have Alexei confined to his bed in agony. Then when Grigóriy steps up, the bleeding stops immediately thus granting the boy instantaneous relief.

Ain't necessarily so.

But someone else might tell the same story just a bit differently. Far from writhing in agony, we hear that Alexei was asleep when Grigóriy went to Tsarina Alexandra and asked to see the boy. Alexandra didn't want to disturb her son, but Grigóriy insisted. So Alexandra - who could never say "no" to Grigóriy - let him in. Then Alexei woke and Grigóriy spoke gentle words. Alexei, we hear, was healed.

Hm. If Alexei was asleep it seems that he was no longer in pain. And if he was no longer in pain, then we have to say the internal bleeding must have stopped. It's not clear, then, exactly what Grigóriy had done. Other than wake the kid up.

We don't want to minimize the seriousness of Alexei's condition, though. One episode was particularly dire. Alexei had slipped and banged his knee. The internal bleeding was severe, Alexei was again confined to bed and his temperature rose to 105o.

The doctors had said there was no hope. And then happened a miracle that only the most rabid (ptui) skeptics will dare question.

Tsarina Alexandra was frantic since Grigóriy was back in Pokrovsky. So in desperation Alexandra sent him a telegram saying that the doctors had said Alexei was doomed. Grigóriy calmly replied by return wire: "The boy will not die," adding "Do not let the physicians bother him too much."

Ignoring the fact that neither telegram survived to be examined by historians, it has been accepted that Grigóriy did send some kind of soothing assurances to the Tsarina. But that the bleeding stopped the next day is suspect since a letter written by Alexandra on the next day said that the doctor saw no improvement. But she did say she was no longer worried.

The truth is that Alexei's recovery was scarcely miraculous. His temperature stayed above 102o for two more days, and he was in frequent and intense pain. He remained in bed for months but did slowly recover.

What's particularly instructive is the people at the time seemed less impressed with Grigóriy's ability in this particular episode than those a century later. Nicholas never mentioned the matter even though he wrote a letter to the family's spiritual advisor Father Alexander Vasiliev. He mentioned the treatment of the doctors but nothing about Grigóriy. And other than Alexandra saying she had been "reassured", she never said she thought Grigóriy's intervention had really helped. In fact, Grigóriy himself never mentioned the matter.

In other words, Alexei's recovery was what you would expect for a serious, but non-fatal bleeding episode of a hemophiliac. Again Grigóriy's healing ability seems to have been limited and we have no evidence of any real cause and effect.

And despite what you may read or hear, Alexei could recover quite well from bleeding episodes without any intervention from Grigóriy. A few weeks after one of Grigóriy's supposed healing sessions, Alexei again slipped. This time he hit his forehead, making this one of his most dangerous accidents and was similar to what caused the deaths of three of Victoria's descendants including her son, Leopold. Leopold had also slipped and hit his head. This produced a cerebral hemorrhage and Leopold died.

Alexei was again put to bed and treated by the physicians. But both Alexandra and Grigóriy were out of town. Nicholas neither called nor contacted Grigóriy, and Alexei recovered.

Finally, we should note the comments about Grigóriy's treatment mentioned by one of the court ladies. She noted that when Grigóriy was called in to help, he seemed to wait a while. It was almost as if he was biding his time until it was clear Alexei was going to recover. Perhaps Grigóriy thought his healing powers might work better with supplemental help from the physicians.

How Did He Do It?

OK. Let's summarize what we know about Grigóriy's healing powers:

Even with his hemophilia, the odds that Alexei would live to at least his early adolescence were quite high.

When Grigóriy intervened, Alexei recovered.

When Grigóriy didn't intervene, Alexei recovered.

So for all the touted "undoubted powers of healing" that talking heads assure us that Grigóriy "must have had", his treatment would certainly not pass muster for efficacy using modern clinical standards. A treatment which has the same effect of doing nothing at all, well, is doing nothing at all.

Now lest Grigóriy's friends go into spittle-flinging diatribes that we are being overly dismissive, we can - and will - cut Grigóriy some slack. But first let's remember the story told by Vance Randolph in his masterful academic study, Pissing in the Snow and other Ozark Folktales.

Vance Randolph

A Masreful Tale

A farmer was having digestive problems and after a particular fetid blast, his wife told him to go to the doctor. Otherwise she and the kids would have to go stay with her folks. The man grumbled but went to the doctor.

After the farmer demonstrated the problem (which drove the other patients out of the office), the doctor cried, "My God! Something must have crawled up inside you and died! What you have to do is go home and eat plenty of garlic, raw onions, and wild ramps for dinner. And before you go to bed, eat half pound of Limburger cheese.

"Do you reckon all that will cure me?" the farmer asked.

"No, I don't think it will cure you," the doctor admitted. "But it might help some.

And we too agree it is possible that Grigóriy's ministrations may have helped some.

Certainly one undoubted benefit was Grigóriy calmed down Alexandra. Calming Alexandra would also calm down Alexei which in turn would decrease the boy's blood pressure, slow the bleeding, and permit a quicker recovery.

And we need to remember that folk healers who supposedly stopped bleeding, particularly in farm animals, were common in Siberia. By some accounts, they would "stroke" the animal near the wound to effect the cure. In other words without actually understanding the physiology, they would gently compress the blood vessels between the wound and the heart. This could reduce or stop even serious bleeding. This is a technique still used by modern medical profesionals and Grigóriy could easily have learned this "power" while young.

And there is some of Grigóriy's advice that fits in perfectly with modern treatment of hemophilia. He told Alexandra to throw out the new wonder-drug which the doctors had been prescribing to relieve Alexei's pain. That was aspirin. Although aspirin is proven effective as an analgesic, it is also proven effective as a blood thinner - not what you want to prescribe for a bleeding episode. In fact, modern advice is for hemophiliacs to avoid aspirin, and so indeed we have something from Grigóriy that may really have helped some.

Most of all we should remember that Grigóriy did not - that's not! not! not! - ever cure Alexei. The Tsarevich continued to suffer from hemophilia for the rest of his life.

The Gift of Prophecy

But hold on! say Grigóriy's fans. Surely you can't doubt Grigóriy had powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men. He had true prophetic abilities to which many witnesses attest. How can any but the most (ptui) rabid skeptic doubt such proof?

There is a major problem when reporting - quote - "prophecies" - unquote - that is often unappreciated. We rarely have a clear cut prediction that is reported until after the event occurs. And after-the-fact predictions cannot be used as evidence that anyone had any unusual ability to predict the future.

A perfect example is the so-called "prediction" or "profile" of the Mad Bomber of New York. We read a psychiatrist predicted with uncanny accuracy the type of person the Bomber was. Among a number of characteristics, we were told the Bomber would be uninterested in women and when arrested he would be wearing a double breasted suit with all the buttons buttoned.

The trouble is that the "prediction" - including about no interest in women and wearing a double breasted suit with the buttons buttoned - was only written down after the Bomber was arrested. And it was written by the psychiatrist himself. It's easy to be accurate that way.

However, in this case, we have a documented prediction before the arrest. Some months before the Bomber was arrested, the New York Times published the psychiatrist's prediction - a prediction that never mentions a double breasted suit and even said the Bomber would be interested in women.

(Today where sticking to facts is now considered a major fault even by our elected leaders, it is amusing to find that the Times data is sometimes "adapted" to fit the after-the-fact prediction. A popular informational website quotes the Times article but inserts the word "not" before "interested". And even in a book about the Bomber, a "not" is added to the quote although it is enclosed in brackets.)

This does not mean that post-event prescience is necessarily out-and-out fraud. What is called "memory deterioration" and "hindsight bias" are normal psychological phenomena that happen to everyone. As time goes on there is a tendency to remember predictions - or guesses as to the future - as being more accurate than they really were. So a true test of unusual prescience must have clear, specific, and testable predictions that were documented before the event occurs.

And a good example of what seems to be a remarkably accurate prediction of the fate of the Romanovs was published while Nicholas, Alexandra, and their kids were still alive. The article stated that Grigóriy predicted that as long as he was alive, their dynasty would rule. Otherwise, the Romanovs would fall.

The author of this interesting but rather flamboyant article was Lincoln Steffens, at that time one of the most interesting and flamboyant journalists in the world. He published the article in late 1917, which as we said was when the Tsar and his family were still alive.

But it was published after Nicholas was no longer Tsar and the monarchy had been abolished. And note that Lincoln only said Grigóriy predicted the Romanovs would fall. No one predicted the Tsar and his family would die. So the prophecy was - after all is said and done - reported only after the event had occurred.

But wait! Don't we have the actual letter Grigóriy wrote? And he did say that the Tsar and his family would die - and even gave the time! Here it is, verbatim and unvarnished, and you can see for yourself its uncanny accuracy:

Дух Григория Ефимовича Распутина Новых из села Покровского.

Я пишу и оставляю это письмо в Петербурге. Я предчувствую, что еще до первого января уйду из жизни. Я хочу Русскому Народу, папе, русской маме, детям и русской земле наказать, что им предпринять. Если меня убьют нанятые убийцы, русские крестьяне, мои братья, то тебе, русский царь, некого опасаться. Оставайся на твоем троне и царствуй. И ты, русский царь, не беспокойся о своих детях. Они еще сотни лет будут править Россией. Если же меня убьют бояре и дворяне и они прольют мою кровь, то их руки останутся замаранными моей кровью, и двадцать пять лет они не смогут отмыть свои руки. Они оставят Россию.Братья восстанут против братьев и будут убивать друг друга, и в течение двадцати пяти лет не будет в стране дворянства.

Русской земли царь, когда ты услышишь звон колоколов, сообщающий тебе о смерти Григория, то знай: если убийство совершили твои родственники, то ни один из твоей семьи, то есть детей и родных не проживет дольше двух лет. Их убьет русский народ. Я ухожу и чувствую в себе Божеское указание сказать русскому царю, как он должен жить после моего исчезновения. Ты должен подумать, все учесть и осторожно действовать. Ты должен заботиться о твоем спасении и сказать твоим родным, что я им заплатил моей жизнью. Меня убьют. Я уже не в живых. Молись, молись. Будь сильным. Заботься о твоем избранном роде.

Григорий

... which with minor editing for a rambling style and to add clarity is translated as:

From Grigóriy Efimovich Raspútin Novykh in the village of Pokrovsky,

Tsar, when you hear the bells ringing, informing you of Grigory's death, then be aware. If the murder was committed by your relatives, then none of your family, that is, children and relatives, will live longer than two years. They will be killed by the Russian people.

Grigóriy

Удивительно! And yes, the entire Romanov family was gunned down by the Communists in Siberia on July 17, 1918 - almost two years afterwards! And the Russia of the Tsars was soon to collapse, never to rise again.

So Grigóriy hit it right on the money!

Oh, yes. There's just one little problem.

No one has ever seen the letter.

Ha? (To quote Shakespeare.) No one?

Nope. No one.

The sad truth is we only know of this letter because it was quoted in a book written by Grigóriy's secretary, Aron Simanovich.

And when did the book appear?

1928.

What? (Again Shakespeare.) 1928?

Yes, 1928.

In other words, this remarkably accurate and uncanny prophecy was written down a decade after the event.

Once more we can't assign a motivation to Aron's after-the-fact prescience. It may simply have been "memory deterioration" and "hindsight bias" and not just a ploy to sell his book. So perhaps Aron did honestly believe he was remembering a letter as Grigóriy actually wrote it.

Perhaps.

The End?

Well, OK. So maybe Grigóriy's healing ability wasn't that remarkable. And maybe his prophetic powers were more impressive if they were reported a decade after the event.

But you can't deny that Grigóriy was a man no one could kill. Due to a dastardly plot, he was poisoned and shot but survived. And it took three days beneath the waters of the frozen Neva River to finished the job.

We know what happened because we have an account - not just by witnesses - but by some of the principals involved. That is, we have the stories by the killers themselves.

The primary mover of the plot was Prince Felix Yusupov. Felix is a pretty interesting fellow. He was born into a rich - very rich - Russian family and studied art at Oxford. In 1914, he married Irina Alexandrovna, who was the niece of the Tsar (in fact, Nicholas himself gave away the bride). Despite Felix's penchant for wearing ladies clothing, the marriage was a happy one and endured over 50 years.

Prince Felix Yusupov

He offered hospitality.

By 1916, Russia was in a tight spot. Following the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and the strange and convoluted series of treaties, alliances, and pacts that ballooned into World War I, Nicholas had aligned himself with his first cousin, King George V of England, to fight his third cousin, Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany.

You'd think Nicholas would have learned. In Russia, war and revolution went hand-in-hand. In 1904 Japan and Russia had been arguing over territory for about ten years. Fed up, Japan finally declared war in February.

After fighting for about a year, Russia had been pretty much whupped. As usual, the citizens were dissatisfied and in January, 1905, riots had broken out. Eventually Nicholas had to agree to the creation of a legislative assembly, the Duma and hired a prime minister. Things eventually simmered down but from then on there were always insurrectionist rumblings around the country.

So in 1914 there was World War I. But by 1916 - America had still not jumped in - the war had gone so badly that the Russian army was in revolt. In the cities food was running out, riots were in the streets, and factory workers had gone on strike.

And then the unimaginable happened. People began yelling for the Tsar to step down.

Of course, people were blaming Grigóriy as well. Look what was happening! While Nicholas was at the front ineffectually taking charge of the army, Grigóriy was calling the shots on the home front. Why, he was even dictating who got the government jobs!

So while thousands of soldiers died and civilians starved, Grigóriy lived in luxury. Not only lived in luxury, but kept making whoopee. Not just with the lady attendants of the bath houses, either. He also attended special parties of high brow ladies and their comely daughters where he was the only male in attendance. His behavior and language to them was crude and improper, said eyewitnesses writing years after the event.

And sukin syn! Grigóriy was actually getting it on with the Tsarina herself!

Huh! What could you expect? Everyone knew that Alexandra was really a German spy. And she and Grigóriy were now plotting to hand over Russia to its enemies!

All of this brouhaha about Alexandra and Grigóriy is certainly bogus - whether it's the mutual whoopee, running the government, and the spying. But reality is often less important than what people think reality is. There were anti-Raspúniks in the royal family itself and Felix had decided to lead the group.

We may be getting ahead of ourselves, but one of the earliest reports stated that Grigóriy was taken into a basement and severely beaten. He was then shot and dumped into the Neva River.

This, of course, isn't the story that everyone tells, and the accounts can get a little confusing. For instance, you will read that Grigóriy was killed on December 16, December 17, December 29, or December 30. Of course, the catholicity of dates is because some people select the day when Grigóriy left his home late at night. Others use the day when he was actually killed in the wee hours of the morning. Also the Russians were still using the Julian Calendar (called "Old Style" or "OS" dates) which was two weeks behind the "New Style" or Gregorian Calendar. We'll use the date the Russians were using - that is, the "Old Style" - and we will say Grigóriy died in the early morning of December 17, 1916.

So with that cleared up, let's review the Gospel According to Felix.

Felix was solely motivated to save Russia from the malignant force that was Grigóriy Raspútin. There were German spies in Grigóriy's entourage who plied him with booze to get information. Not that such artificial methods were needed since Grigóriy gave away the information willingly. Grigóriy was also dictating who was appointed as government officials and military leaders and was denigrating patriarchs of the Church.

And above all, Grigóriy had ordered the doctors to administer drugs to Nicholas that would weaken him to the point that he would have to step down from the throne. Then Alexei would become Tsar. But since Alexei was seriously ill and a minor, Alexandra would become the crown regent and so Grigóriy would be the effective ruler of the country. He would then negotiate a separate peace with Germany which would destroy Russia.

Of course, there is another story that Grigóriy hit up on Irina at a party which ticked Felix off.

Whatever the motivation, Felix did not act alone. Instead he brought in four of his buddies. These were the cousin of the Tsar, The Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov, as well as Duma deputy and all around мудак, Vladimir Purishkevich. There was also the physician Stanislaus Lazovert and an army officer named Sergei Sukhotin. Together they hatched the plan.

Naturally, they had to get Grigóriy alone. So Felix offered him the hospitality of his Moika Palace which is now a museum in St. Petersburg. But Felix figured committing murder in his living room might upset the rest of the household. So he had the servants fix up the basement so it looked like an opulent parlour suitable for a private visit from the advisor of the Tsar and Tsarina.

Of course, they had to get Grigóriy to the palace. Some accounts say that Grigóriy had been promised some hot babes for his pleasure. But almost twenty years later Felix said he had arranged a small dinner party with Grigóriy so he could meet Irina. This story sort of agrees with Lincoln's 1917 article. Maria Rasputin, on the other hand, said that Felix asked her dad to come and use his healing powers because Irina had a headache.

The rendevous was set for late in the night. This wasn't unusual as high-class parties often began after 10:00 p. m. and continued until almost daybreak. So the conspirators had plenty of time to set things up.

Dr. Lazovert - always conscious of safety - put on rubber gloves and took some cyanide crystals and began to grind them to a fine powder. He then lifted up the layers of the small cakes and sprinkled the inside with the poison. The icing was color-coded so everyone else would know which cakes not to take. Dr. Lazovert assured everyone that each pastry had enough poison to kill several men.

They also added cyanide to some empty glasses - enough poison to do the job but not be easily visible in the dim light. This way Felix could select any wine and then simply pour it into one of the spiked glasses. Then he could pour his own drink into a clean goblet and not arouse suspicion.

About 10:30 Felix got into his car and drove to Grigóriy's residence. He went to the back door and after some difficulty in getting admission was let in. Then he drove Grigóriy back to Moika.

After they were settled comfortably in the now opulent basement, Felix offered his guest some of the cakes. At first declining them because they would be too sweet, Grigóriy finally selected one and wolfed it down. Expecting Grigóriy to keel over, Felix was surprised when after consuming even more cakes, Grigóriy appeared quite unaffected.

Perhaps, Felix suggested, Grigóriy would like to sample some of his fine Crimean wine? A little Madeira, if you don't mind, Grigóriy replied. He took the glass - laced with the cyanide - and downed it.

Nothing. Grigóriy calmly walked about the room. He noticed Felix had a guitar and asked him to play something. Felix played what he called a "ditty", but his heart wasn't in it.

It was now 2:30 a. m., and the others upstairs were getting antsy. They began moving around and Grigóriy, hearing the noises, asked what was up. Felix said it was probably some other guests of the family leaving. He'd go and check.

Felix went upstairs and told the others that Grigóriy was still alive. What do do?

Enough over-planned schemes, they decided. They would go down en masse. Then they would jump Grigóriy and strangle him. No sweat.

But as the group moved downstairs, they worried that the sudden appearance of a group of hitherto unannounced men would tip Grigóriy that something was up. Despite the four-to-one odds, they were afraid that with his undeniable energy, Grigóriy might get away. Taking a pistol from Dmitri, Felix went back downstairs.

Alone once more with his unsuspecting and uncooperative guest, Felix stopped to look at a crystal crucifix. Grigóriy, probably wondering when his feminine companions were going to show up, asked what he was doing. Felix said he liked the crucifix. Grigóriy walked toward Felix and said he liked one of the cabinets better.

"Grigóriy Efimovitch," he said, "you'd far better look at the crucifix and say a prayer."

Rather than take alarm at what was clearly a melodramatic threat, Grigóriy just moved closer and looked Felix in the eye. Then he glanced back at the crucifix. Felix, not knowing whether he should shoot his guest in the head or the heart, pulled his gun and shot at Grigóriy's heart.

Hearing the bang, the others burst in the room. After examining the now supine form, Stanislaus ventured his official medical opinion that Grigóriy was dead.

The men turned off the light (yes, they had electric lights) and went back upstairs. Their plan was to take the body to the Neva River's Petrovsky Island which is now the site of a professional sports stadium. There was, though, no real hurry, and they had a few drinks.

Suddenly Felix had misgivings. Leaving the others, he went back downstairs and checked Grigóriy's pulse. Nothing. Then for some reason, he grabbed and shook the "lifeless" form.

Dr. Stanislaus's professional opinion notwithstanding, Grigóriy's eyes flicked open. "Foaming at the mouth", he leapt for Felix, grabbing him by the throat and ripping off one of his epaulets. Felix yelled for help and managed to break free of Grigóriy's grasp.

Felix dashed upstairs and found the others on the way down. When they reached the basement they found Grigóriy heading out an alternate exit. While the others bounded outside, Felix grabbed a lead-weighted rubber truncheon - evidently no nobleman's palace should be without one. But before he could get outside, he heard four shots.

Grigóriy had made it to the courtyard and had been heading toward one of the gates. Vladimir claimed it was he who fired the shots, and Grigóriy again fell dead - again.

Of course, shooting guns in your backyard can attract attention. The servants ran downstairs and asked what was going on. Oh, nothing Felix laughed. Just some horseplay.

Clearly the Moika Palace wasn't the best location for a assassination plot gone awry. There was a police station just a little ways off, and the cops suddenly showed up. Felix later claimed that Vladmir told them what happened, that they had killed Grigóriy. But it was for the good of the country, he added. No problem, the police said politely and left. Felix later said he told the servants the truth, and they, too, agreed to keep quiet.

And Grigóriy? Well, the conspirators bundled him into the trunk of the car and drove a mile north to the Petrovsky Bridge where they dumped the body. But when he was finally discovered, the doctors found that Grigóriy Raspútin - after being poisoned and shot - had actually died of drowning.

This, then, is the story we usually hear. But we also saw that one of the earliest reports said the truth was more mundane. Grigóriy was simply beaten and shot.

What, we asked, really happened?

Well, let's turn to a recent biography that summarized the known facts.

- In the early morning of December 17 (OS) Grigóriy was killed after visiting the home of Felix Yusupov.

- His body was dumped in the river.

That's what we know for sure.

For years one really questioned the story about the poisoned cakes and wine. It was too good a story to deny. But in 1995, a bundle of papers were offered for auction at Sotheby's. They were, in fact, a bunch of documents from an investigation conducted by the Russian government about the doings of the Tsar and his family. Naturally the report had much about Grigóriy and included the autopsy report with photographs of Grigóriy after he was pulled out of the river.

The summaries you read in the various accounts are - as always - inconsistent and you wonder if the authors were reading the same documents. Some accounts will tell you there was water in Grigóriy's lungs. Others that there was none. Sometimes you'll read there was a "little" water.

You will also read that the report explicitly stated there was no poison in Grigóriy's body. Still others quote the report and don't mention poison one way or the other. One - quote - "first hand report" - unquote - did state there was no poison - but it was written in 1935. Lincoln's article - which you'll remember was written in 1917 - stated that there was poison in Grigóriy's stomach but it had actually remained stuck in the cakes.

One thing is clear. There were signs of physical abuse beyond anything Felix said. There had been blows to the head and body and what Pliny the Younger referred to as "the parts that are held in reverence" had been smashed flat. There was also no evidence, as you may read on the Fount of All Knowledge, that any portion had been detached and kept as a pickled, but impressive relic.

But the physician who conducted the autopsy, Dr. Dimitry Kosorotov, said without equivocation that the cause of death was the bullet to the head and that Grigóriy was dead before he hit the water. So for all the talk about poisoned cakes, wine, and a robust Grigóriy finally drowning in the river, it looks for the world that he had been beaten savagely and then shot - much like the original memo had said.

Not that the autopsy cleared up everything. Dr. Dimitry stated that the bullet wounds had come from three different handguns of different calibre. He was hit once in the side, once in the back, and finally in the forehead. There is also independent evidence that there were shots fired outside of the palace. Grigóriy may indeed have made a break for it and was brought down outside as Felix had said.

Although Felix gave the impression they had planned everything carefully, there was a lot they hadn't considered. For one thing Grigóriy was no fool. He had told both his daughter, Maria, then living with her dad, and his secretary, Aron Simanovich, that he would be going over to Felix's. Maria even said she recognized Felix when he came to pick Grigóriy up.

When the day dawned, Maria, then nineteen, began to worry. Still, since her dad often came home at odd hours, she just decided to wait.

Aron, though, thought something was up. Grigóriy had said he'd give him a call later to let him know he was all right (and yes, they even had telephones). When he didn't, Aron called the cops.

Rumors, though, were already out that Grigóriy had been shot - not surprising when you consider gunfire had been reverberating around Felix's neighborhood. It also wasn't great for secrecy that Vladimir Purishkevich began to blab to some soldiers he was the hero who had killed Raspútin.

So within a few hours of the murder, an investigation was called. One story is Alexander Protopopov, the Minister of the Interior, ordered General Pyotr Popov to begin an official investigation. Another account is that an official in the ministry of justice, Sergei Savadsky, Procurator of the Appellate Court, began the investigation.

Among the Sotheby's documents are actual police reports of the investigation, and it looks like even by modern standards, the investigators did a proper and efficient job. They first contacted the people who had last seen the victim. So Pyotr quickly spoke to Maria and immediately had the suspects in his sights.

Maria had told them that her dad had gone over to the Moika Palace. Yes, she had actually seen Felix and recognized him when he came to pick Grigóriy up. The maid also said she saw Felix and that the two men left together.

The investigators then spoke to the policemen of Felix's neighborhood and were able to confirm four or five shots had been fired in the early morning. The nightwatchman of the palace also confirmed he heard gunfire.

The news spread fast - and far. By the next day, December 18, the head of British Intelligence, Sir C. Mansfield Cumming (who signed his memos "C" in green ink), was told that Grigóriy was dead. That same day Felix was formally questioned.

He adamantly denied meeting Grigóriy. They had spoken by telephone, yes, and Grigóriy had wanted to meet his wife. But he, Felix, had put him off. The last thing Felix wanted was Grigóriy bothering Irina particularly since Felix said that over the phone he heard the sounds of partying including "female squeals".

By now, of course, Nicholas and Alexandra had been told that Grigóriy was missing. What was worse was they were hearing - correctly as it turned out - that family members were involved. Not just Felix but the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich. Dmitri also denied everything but admitted he had been at the Moika Palace for dinner.

In the meantime, the police had ordered a search for Grigóriy. They quickly found a rubber boot in the river and showed it to Maria. She confirmed it was her dad's.

Then on December 19, guards noticed something a little ways downstream from the Petrovsky Bridge. Some accounts say it was a body-shaped form under the water; others that it was an overcoat. But whatever the guards thought they saw, when it was chipped out of the ice, it was Grigóriy, well-chilled and preserved, but rather the worse for wear.

Life After Grigóriy

Despite the denials by Felix and the others, there wasn't really much doubt who was guilty. Soon they confessed.

And you can imagine what happened to THEM!

Yep. Absolutely nothing. All proceedings were halted by order of Nicholas.

So just why did Nicholas shrug off what was a savage murder of one of his family's trusted advisors?

Actually he didn't. He expected the investigation to proceed and the guilty brought to justice. But then he had a visit from his brother-in-law, Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich who had married Nicholas's sister, Xenia. Alexander - whose friends called him Sandro - also happened to be Felix's father-in-law.

Sandro urged Nicholas to take no action against Felix and the rest. Instead, treat them as "misguided patriots" and let them go.

"A very nice speech, Sandro," Nicholas said, "Are you aware, however, that nobody has the right to kill, be it grand duke or a peasant?"

Sandro's recommendation had irritated Nicholas, yes. But what sent him into spittle-flinging diatribes was when sixteen others of his family members wrote asking him to let things drop. One letter even came from his mother, for crying out loud!

Everyone except Nicholas had become convinced that that public opinion had run so high against Grigóriy that any action against his killers would lead to open revolt. Finally Nicholas bowed to the family's pressure and stopped further proceedings.

We hear that Alexandra actually smacked Nicholas when she heard he had dropped any action against Felix and his buddies. For his part, Nicholas was probably glad to have Grigóriy out of the picture. He really knew that Grigóriy's main value had been to calm Alexandra when no one else could. "Better ten Raspútins than one of the Empress's hysterical fits," he once grumped.

Saying that public opinion was running against Grigóriy is true only in a limited sense. Even today "public opinion" often refers to sampling of the higher echelons of the population. So sometimes we find the average citizen doesn't agree with what the pundits say is public opinion.

So it seems with opinions about Grigóriy. The ordinary Russian had begun to see him not as a sinister influence on the Royal Family but as a man of the people who had finally made it to the inner circles of the Tsar. At least Grigóriy understood the trials and tribulations of the average Iosif and Zhozefina on the street, and his murder was just one more example of how the Russian fat cats were keeping the people in subjugation.

In any case, regardless of whether the people thought Grigóriy was good or bad, Nicholas and his friends had a lot to worry about. By the end of 1916, Russia and its government had fallen apart and those pesky fellows called the Bolsheviks were massing a real following. Then in February 1917, the Tsar finally bowed to the inevitable and abdicated to his brother Michael, who immediately turned down the job.

Mr. Ulyanov

He took over.

That left the country in charge of the Duma and Prime Minister Georgy Lvov. Georgy's government didn't last long. In October and with the help and acquiescence of the Germans, Vladimir Ulyanov - who wrote under the pen name "Lenin" - took a train into St. Petersburg which had been renamed Petrograd. The Winter Palace was taken over - "stormed" is not quite what you call a group of untrained civilians walking into a building guarded by military cadets - and eventually Lenin and his friends were in charge.

Any of the Romanovs who managed to survive the Communist Revolution - which did not include Nicholas, Alexandra, or any of their kids - did so by leaving the country. Felix and Irina managed to "git" and eventually settled in Paris.

Over the past century a number of authors have looked into ...

THE TRUTH ABOUT

THE DEATH OF RASPÚTIN

... and come up with various theories.

The real reason Felix bumped Grigóriy off, we learn, was that Felix had been involved in too much masculine togetherness and Grigóriy had tattled to Nicholas. Others think it was really the Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich - who we haven't mentioned - who was really the mastermind of the plot.

Both of these alternative theories are unlikely. Grigóriy probably didn't know anything about Felix's private life that the Tsar didn't know already. And the reason people think Nicholas Mikhailovich was involved is that he wrote in his diary where he pondered killing Grigóriy. But it's pretty obvious that a lot of people were thinking the same thing. There's no evidence that Nicholas Mikhailovich ever put his thoughts into action.

In 2015 a book was published where it was pointed out that there were some cryptic comments in the files of British Intelligence that suggested that the British were not only interested in getting rid of Grigóriy, but may have had an active hand in it. One story is that there was even a British agent in the party that dispatched Grigóriy. And the bullet wound in the forehead has been identified arising from a .38 calibre Webley revolver - a British handgun.

Actually, the idea that the British were in the plot was nothing new. Almost as soon as Grigóriy was killed a German spy reported that there had been an Englishman in the group. Others have hinted that Scotland Yard was involved and in 1934 an English MP even confessed he had been asked to kill Grigóriy.

Of course, all of this proves nothing. But some serious students think that the British being involved - if not certain - deserves serious consideration. The hands-on guy - whom some believe actually issued the coup-de-grace - may have been British intelligence operative Oswald Rayner. Oswald, it turns out, had been a good friend of Felix and had met him when they were students at Oxford.

Other historians are not convinced. One of Grigóriy's recent biographers has pointed out that Grigóriy's death was the result of one of the most bungling homicides ever committed. Surely professional intelligence operatives would have done the job better.

Surely.

As we said Felix and Irina went to Paris. But after finding himself short of cash - job opportunities for former Russian aristocrats has always been limited - Felix wrote some not always consistent memoirs. His last book, Lost Splendor, was published in 1953. Felix never departed from his story about the poisoned cakes and spiked wine, and he died in Paris in 1967. Irina followed a few years later.

And what of Maria, Grigóiry's daughter? Well, her life - if not one of glitter and ease - was at least interesting.

It's no surprise that when Grigóriy was dead Maria found that the idolizing crowds quickly vanished. She had one last visit with the Tsar's family where she and her sister Varvara were advised to high-tail it - at least from St. Petersberg.

So the girls returned home to Pokrovsky where their mom still lived. Maria married a young man named Boris Soloviev who himself was imprisoned by the Communists. But Maria got him out by bribing a guard. Or so the story goes.

The couple escaped to Europe. Completely impoverished, Boris took menial jobs and died in 1926. Maria's sister, Varvra, had remained in Russia and had died two years earlier.

Maria and Boris had two daughters, Tatanya and namesake Maria. To support the now fatherless girls, Maria took a job as a factotum for a rich Russian expatriate. The pay wasn't much and she struggled to support the girls. Then suddenly her fortunes changed.

Not a lot but at least for the better. Still in her twenties, she was offered a job as a dancer in a night club. She had no illusions was to why she was given the job. Her name and history were a big draw. But it beat keeping house in Paris.

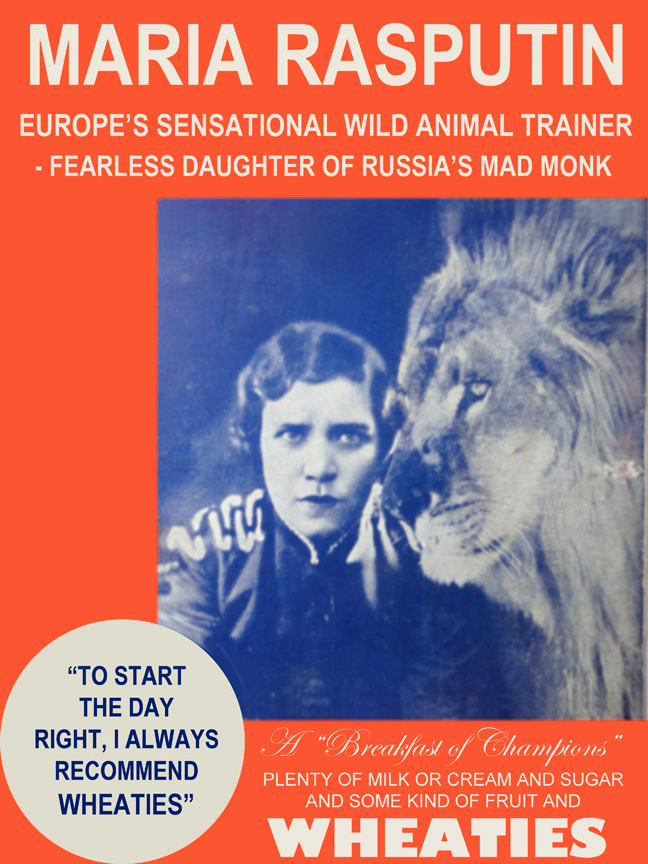

She wasn't getting any younger, though. But then she was offered a job as an animal trainer in a circus. Again the Raspútin name brought in customers, and in 1935 she was hired by Ringling Brothers for an American tour.

Of course, she also wrote books where she defended her dad's memory. He was a simple unaffected man, she said, much maligned and misunderstood.

Maria remained in America and married a man she had known in Russia. The marriage was unhappy and her husband finally just walked out. With America now gearing up for World War II, Maria got a job as a machinist in a California shipyard. The pay was good, and two years after the war, she became a naturalized US citizen.

After Maria retired, she lived mostly on social security. Then in 1977 and nearly age either 79 or 80, she and a journalist wrote her last book, Rasputin: The Man Behind the Myth. Once more she told everyone how her dad was unjustly villified. She died later that year.

In the end, then, Maria, who once rubbed elbows with Imperial Russia's highest families, had become thoroughly Americanized. True, in the 1950's there had been rumblings that she had harbored communist sympathies - a charge she vehemently denied. There could be no doubt of her loyalty, however.

After all, no one but a true American would ever appear on a box of Wheaties!

Maria Raspútin

Proof of Loyalty

References

Rasputin: A Life, Joseph Fuhrmann, Praeger, 1989.

Rasputin, Douglas Smith, Macmillan, 2016. A more recent biography.

The Romanov Sisters: The Lost Lives of the Daughters of Nicholas and Alexandra, Helen Rappaport, St. Martin's Press, 2012.

Rasputin i yevrei: vospominaniya lichnogo sekretarya Grigoriya Rasputina, Aron Simanovich, 1928, Riga. Modern (and English) translations are available and the original Russian is online:

Распутин и евреи Воспоминания личного секретаря Григория Распутина, Арон Симанович , http://emalkrest.narod.ru/txt/rasp/simanov.htm.

"The Mad Monk: The Life and Death of Rasputin as Revealed by Newly Released K.G.B. Files", Robert Daniels, The New York Times, June 11, 2000.

To Kill Rasputin: The Life and Death of Grigori Rasputin, Andrew Cook, The History Press Ltd., 2007

The Rasputin File, Edvard Radzinsky, Doubleday-Talese, 2000.

Rasputin: The Role of Britain's Secret Service in His Torture and Murder, Richard Cullen, Dialogue, 2010.

"The Killing of Rasputin", Lincoln Steffens, Everybody's Magazine, Volume 32, Issue 4, October 1917, pp. 385 - 394. One of the earliest accounts of Grigóriy's death.

"The Assasination of Rasputin: Prince Tells How He Killed Russian Tyrant", Glascow Hearld, March 1, 1934.

"The Many Lives of Maria Rasputin, Daughter of the 'Mad Monk'", Hadley Meares, Atlas Obscura, November 4, 2015. A very good article.

Maria Rasputin Bern, Insisted She Was Child of 'Mad Monk;", The New York Times, September 29, 1977.

Lost Splendor, Prince Felix Youssoupoff, Putnam, 1953. Today most English speakers spell Felix's last name something like "Yusupov" but the longer speller is how it first appeared in the book. The Russian spelling is Юсупов. There are subsequent editions of Felix's book.

Rasputin: The Man Behind the Myth - A Personal Memoir, Maria Rasputin, Patte Barham, Prentice-Hall, 1977. This is Maria's book.

Rasputin, Jack Perkins (presenter), Arts and Entertainment, 1977. An example of a show about Grigóriy.

Alexander Palace Time Machine: The Home of the Last Tsar - Romanov and Russian History, http://www.alexanderpalace.org/palace/. A nice website about the history of the Tsars.

"Haemophilia in the Descendants of Queen Victoria", English Monarchs, www.englishmonarchs.co.uk.

"Case Closed: Famous Royals Suffered From Hemophilia", Science Magazine,

"Genotype Analysis Identifies the Cause of the 'Royal Disease'", Evgeny Rogaev, Anastasia Grigorenko, Gulnaz Faskhutdinova1, Ellen L. W. Kittler1, and Yuri K. Moliaka, Science, Vol. 326, Issue 5954, pp. 817

An Introduction to the Bootstrap, Bradley Efron, Robert Tibshirani, R. J. Tibshirani, Taylor Francis Ltd, 1994. If you want to do the calculations about how much Grigóriy did or did not help Alexei, this book give the basics of the method.

"Hemophilia B", National Hemophilia Foundation, https://www.hemophilia.org/Bleeding-Disorders/Types-of-Bleeding-Disorders/Hemophilia-B

"Hemophilia B", DoveMed, http://www.dovemed.com/hemophilia-b/

"Life Expectancy of Swedish Haemophiliacs: 1831 - 1980", S. A. Larsson, British Journal of Haematology, Vol. 69, Issue 4, pp. 593 - 602, April, 1985.

"Rasputin's Murder", Alexander Palace Time Machine, http://forum.alexanderpalace.org/index.php?topic=1363.0. A discussion where some of the contributors are highly qualified to offer opinions.

"What is Hemophilia?", Word Federation of Hemophilia, https://www.wfh.org/en/page.aspx?pid=646

"Queen Victoria", Qi.com, http://qi.com/infocloud/queen-victoria

"Europe's Sensational Wild Animal Trainer - Fearless Daughter of Russia's Mad Monk", Wheaties: A Breakfast of Champions, General Mills, 1935. Maria seems to omitted from all the "Athletes on Wheaties" lists you see floating around. What an injustice! The image posted in this essay is actually a graphical rendering of the famous Wheaties box. The fonts may vary a bit but it's faithful enough.

An Introduction to the Bootstrap, Bradley Efron, Robert Tibshirani, R. J. Tibshirani, Taylor Francis Ltd, 1994. If you want to do the calculations about how much Grigóriy did or did not help Alexei, this book give the basics of the method.

Return to Grigóriy Raspútin Caricature